By Ted Lipien

Secession, aggression, and threats at large.

Rebellions, upheavals, and street fights at hand.

How frightening it is to be in charge

Of this vast and terrible land!What seemed immortal is now dead.

What had not existed now abounds.

May God not allow what I fervently dread –

That the winds of yore return on their rounds.

— Natalia Clarkson

A short poem originally written in Russian by Natalia “Natasha” Clarkson sums up her own skeptical views on violent revolutions in Russia’s past. Born from new ideas, erasing old ones from human memory with the help of murder and propaganda, revolutions feeding on group hatred leave behind millions of dead victims before their leaders are themselves killed or pushed aside by history. That’s what Natasha Clarkson, former Voice of America (VOA) Russian Service Chief, would like everyone to remember about the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia on its one hundredth anniversary. A prayer that no one should have to experience again what the Communists did to the country of her parents and grandparents.

Natalia Clarkson’s father lived through the October Revolution in Russia in 1917, or as she aptly corrects its name, a Bolshevik coup. It was eventually followed by a revolutionary transformation of Russia through the Red Terror as the Communists went about defeating their enemies and consolidating their power. But the October events in Petrograd were far from a grassroots revolt they later presented it to be. That happened earlier, in the February Revolution of 1917 in which the Bolsheviks played no major role. Contrary to later claims of communist propaganda, there was not much fighting in Petrograd during the Bolshevik coup.

In October 1917, the Bolsheviks were hardly a majority in largely Christian Orthodox Russia. They did not enjoy popular support among the Russian peasantry whose lands they would soon confiscate and exterminate or starve to death those who offered any resistance. Others would be shot or sent to the forced labor camps of the Gulag for simply being members of the wrong social class, whether they were Russians, Ukrainians or belonging to other nationalities and groups. Natasha Clarkson’s poem speaks of the ever present threat of dark ideas. They lurk in shallow minds of evil men to inspire violent upheavals and murder.

The anniversary of the October Bolshevik Revolution is observed on November 7. It is called the October Revolution because Russia in 1917 was still on the Julian calendar and did not switch to the Gregorian calendar until later. The 11 days difference took the “October Revolution” into November. Supposedly, the cruiser Aurora fired the blank shot that started the attack on the Russian Provisional Government led by Alexander Fyodorovich Kerensky. However, Natasha’s father who was then in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg, Leningrad) heard no such shot, she said.

“Opinions differ even now about the truth of this tale,” Natasha Clarkson told the Voice of America Russian Service journalists Vadim Massalskiy, Sergey Moskalev and Sergey Sokolov in a multi-hour television interview recorded in 2017 at her home in the Washington, D.C. area. Only several minutes of this lengthy conversation made it into a VOA video report, Наталия Кларксон – «прабабушка русской контрреволюции», posted online.

Natalia Clarkson says in the VOA video that on the night of the Bolsheviks’ takeover of the Winter Palace, her father was in Petrograd staying at a hotel. With Kerensky out of the city, there was hardly any resistance to the coup. The next morning, a valet told Natasha’s father that Russia had a new government. Her father would later serve as an officer in the White Army of General Anton Ivanovich Denikin.

Before the revolution, the von Meyer family was well-off and well-connected in tsarist Russia. Under the Russian Tsar, Natasha von Meyer’s maternal step grandfather Sergei Tverskoy followed Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin (Russia’s Prime Minister 1906-1911) as Governor of Saratov, a major port on the Volga River. Her paternal grandfather’s (Konstantin von Meyer ) last appointment was that of the administrator of the tsar’s estate in Turkmenistan. They both survived the 1917 revolution and emigrated to Yugoslavia and France. Natalia was born in Belgrade. Clarkson is the name of her late American husband. There was an ambiguous reference in the VOA video report to the “large Russian-American family Meyer Clarkson,” but Mr. Clarkson was not in the picture in Russia. He was a descendant of one of General George Washington’s aides-de-camp.

Natalia Clarkson being interviewed by Voice of America Russian Service in 2017.

At the end World War II, the von Meyers wound up in Munich, Germany, where in 1952 Natalia was hired by the European bureau of the Voice of America. She told VOA how excited she was when she had a chance to meet in Munich Alexander Kerensky, former Prime Minister in the period between February and October 1917. But when she shared her excitement with her grandmother, the elderly Russian lady told her with a stern look on her face: “go to the bathroom and wash your hands.” She could not forgive Kerensky–as she told the story to Natalia–for receiving her once in his office with his foot on his desk and drinking a glass of milk. It was completely unbecoming for a gentleman to behave in such a way in the presence of a Russian lady, she said. But Kerensky was also generally disliked by the White Russians. They saw him as responsible for the country falling to the Bolsheviks. He indulged them and failed to clamp down on their assaults on parliamentary democracy when they still could have been stopped. Once in power, they did not return the favor.

After coming to the U.S. in 1953, Natalia Clarkson joined VOA in Washington and worked with intervals for raising her children until her retirement in 1997. Starting as a typist in 1952, she held many positions in the VOA Russian Service: news writer, feature writer, editor, broadcaster, senior editor, team leader, programs chief, and finally Chief of the Russian Service. After being “kicked upstairs” by senior management to the USSR Division as Program Manager, she produced five weekly talk shows on international affairs, human rights, and economics. Although Natalia Clarkson did not tell me this, such was the fate of many other journalists I knew who had worked for VOA’s foreign language services and had disagreements with senior management over program policy. 1 She did mention to me there were problems with getting some newly-hired immigrant broadcasters from the Soviet Union to adjust to work at the Voice of America. Soviet ideas of work were not compatible with American ideas. Natalia has written a 400 pages long autobiography which was just printed in a limited and private edition, strictly for the family. Even her best friends do not have copies. But no one has to worry. There is nothing nasty about her VOA colleagues, she assured me. She does not believe in criticizing the people and the organization for which she had worked for several decades.

At the beginning of her radio career, Natalia Clarkson was among some of the first employees of Voice of America Russian Service just a few years after it was established in New York in 1947. As strange as it may seem now, during World War II, VOA did not broadcast in Russian. The Franklin Delano Roosevelt administration did not want to initiate VOA Russian broadcasts in order to avoid offending Josef Stalin in any way, while at the same time closely coordinating American propaganda with Soviet propaganda for VOA programs in other languages. The Russian Service did not yet exist then. 2 To the great disappointment and sometimes horror of many non-communist listeners to VOA wartime programs in German, English, French, Italian, Greek, Polish, Serbo-Croatian and in other languages, they were then then full of pro-Soviet propaganda, extolling Stalin as a radical democrat, covering up his crimes, and promoting establishment of communist governments in Central and Eastern Europe. Many of the early VOA leaders and journalists were open admirers of Stalin and the Soviet Union. A few ended up working after the war as anti-American propagandists for communist regimes in the Soviet block. One was from Poland and another one from Czechoslovakia. None of them were Russians. 3

When Natalia Clarkson joined the newly-established Russian Service in the early 1950s after it was relocated from New York to Washington, VOA under new American management in the U.S. State Department had already acquired by then an anti-communist tone. Under its Service Chief Alexander Grigoryevich Barmin, a Red Army general who had defected in 1937 and became a tireless critic of communism, the Russian Service was not reluctant to report on Soviet forced labor camps and human rights abuses. But in the 1970s, during the Nixon and Ford administrations’ policy of détente toward the Soviet Union, VOA’s senior American management once again resorted to censorship to protect Soviet leaders from criticism. Radio Liberty in Munich managed to avoid most of such program policy restrictions originating from Washington.

Those were difficult times for VOA journalists and for dissidents in the Soviet Union. Victor Franzusoff, Natalia Clarkson’s predecessor as VOA Russian Service Chief, received an order in 1974 from the upper management not to interview Nobel laureate Alexandr Solzhenitsyn. He was also told later by his American bosses not to allow Solzhenitsyn to read from The Gulag Archipelago for VOA’s Russian listeners. 4

The Russian Service journalists remained committed to exposing the horrors of communism, but what the then senior leadership of the Voice of America was afraid of under the pressure of relentless propaganda and intimidation from Soviet media and Soviet leaders were Solzhenitsyn’s descriptions in The Gulag Archipelago of the brutality of the Bolshevik regime and how they could affect the policy of détente with the Soviet block. In his book, the author cited one estimate showing that internal repression in the Soviet Union “from the beginning of the October Revolution up to 1959 had cost a total of…sixty-six million–66,000,000–lives.” 5

“Purging the Russian land of all kinds of harmful insects” was started by Lenin, who wrote those words, and perfected by Stalin. 6 “Insects” included class enemies, malingering workers, and intellectual saboteurs. 7 The number of victims of all communist revolutions worldwide is equally frightening, although Solzhenitsyn noted in his book that there was no official figure. Nixon, Ford and their Secretary of State Henry Kissinger did not want VOA to publicize such information. The U.S. administration cowered under Soviet propaganda attacks on Solzhenitsyn by imposing a ban on him at the Voice of America, while reluctantly allowing Radio Liberty to continue lengthy readings from The Gulag Archipelago. VOA Russian Service journalists were aghast but powerless. They tried repeatedly to get the American management to lift the ban. But not even strong criticism in Congress and in U.S. media could help Russian Service broadcasters for several years. 8

The Voice of America management’s ban on Solzhenitsyn’s participation in VOA programs lasted for several years. Then Solzhenitsyn refused to have anything to do with the Voice of America. Finally, the Ronald Reagan administration brought about a reconciliation between Solzhenitsyn and VOA. In 1984, Mark Pomar who was then VOA Russian Service Chief and USSR Division Director traveled to Solzhenitsyn’s home in Vermont to interview him and record him reading from August 1914, one of The Red Wheel cycle of his historical novels about the period leading up to and including the October Revolution. The Russian Service broadcasts these excerpts over a period of several months. 9

This part of VOA’s history as it relates to Russia, VOA’s initial shameful censorship of Solzhenitsyn and the estimates of the numbers of victims of communism were not covered by the narrators in the 2017 four-minute Russian Service video. But without mentioning this history, the reporters did focus at some length on Natalia Clarkson’s initiative to do another recording of Solzhenitsyn for VOA in 1987.

Because of the approaching 70th anniversary of both the February Revolution and the October Revolution, Clarkson who was then Chief of the Russian Service, came up with the idea of getting Solzhenitsyn to read excerpts from his March 1917 book about the first Russian revolution in 1917. She wanted to show that while the second uprising was in reality a coup by a small group of communists who lacked any popular support in Russia, the February 1917 Revolution O.S. (March N.S.) was a genuinely grassroots revolt and what could have become a democratic transformation.

The VOA report did not mention this and she may not have discussed it with the reporters, but Natalia Clarkson was concerned that if she herself chose the excerpts for Solzhenitsyn to read, either he might be offended, or some of his critics in the West, inspired by KGB smears and propaganda campaigns against him, could find a new reason to attack him with even greater ferocity. She told me she was relieved when Solzhenitsyn’s wife, Natalia Dmitriyevna Solzhenitsyn, had informed her that her husband would himself select parts of his book to be recorded. 10

In 1987, Natalia Clarkson and VOA sound engineer Bob Cole traveled to Vermont to do the recordings which took about two weeks. They were both warmly received by Alexander and Natalia Solzhenitsyn.

Also not mentioned in the short VOA video and perhaps not discussed with VOA reporters was the writer’s insistence that Natalia Clarkson must be a guest at the Solzhenitsyns’ home in Vermont. “I will not allow a Russian lady to stay alone in a hotel,” he had told her, as she recalled in a phone conversation with me in October 2017. She stayed at the Solzhenitsyns’ house for the entire time and ate meals with the family.

Natalia Clarkson also mentioned that Alexandr Solzhenitsyn took a liking to VOA sound engineer Bob Cole. After being a target of constant KGB operations designed to harass him and his family, Solzhenitsyn lived in Vermont in relative isolation, especially from Americans. Being able to talk without fear to a native born American man about the life of average Americans seemed to interest greatly the Russian writer. 11

The VOA video mentions that she was once called by a “Soviet journalist” (VOA should have used the term “propagandist”) the “great-grandmother of the Russian counter-revolution.” She responded that it was a propaganda “compliment” she did not deserve or want.

Natalia Clarkson thinks of her work in the Voice of America as a journalist in the service of a peaceful and democratic transformation. She does not believe in revolutions. After seeing what the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution did to Russia and the rest of the world, one could hardly blame her.

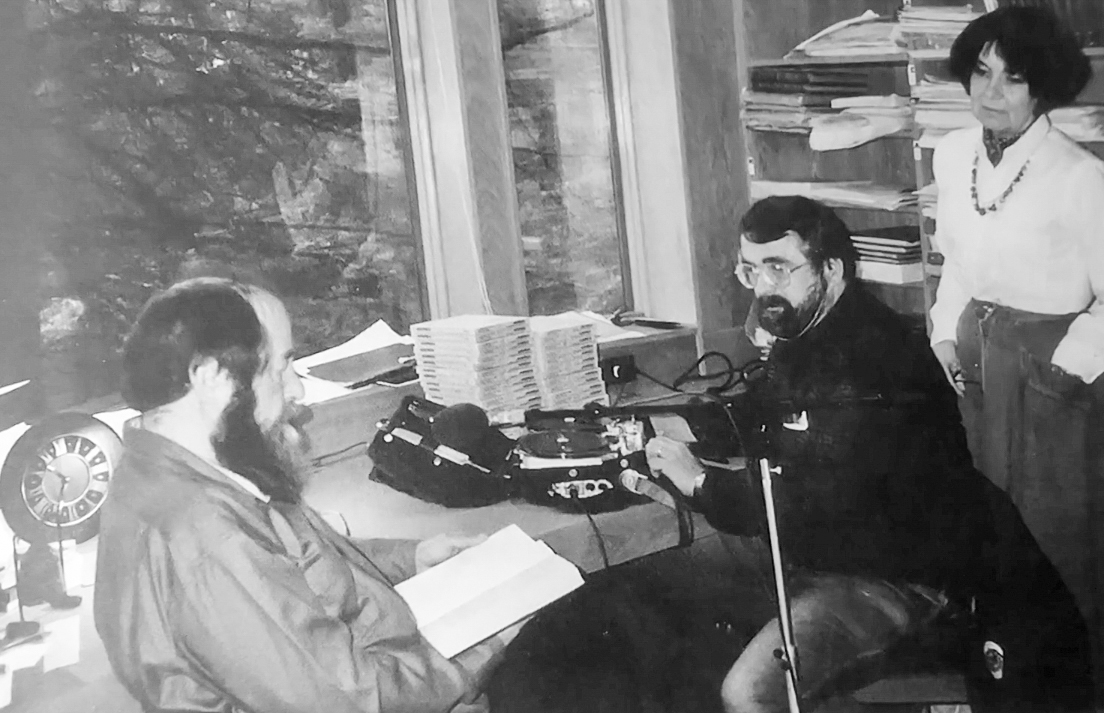

Alexandr Solzhenitsyn reading from March 1917, part of The Red Wheel cycle of novels on the fall of Imperial Russia. Voice of America Russian Branch chief Natalia Clarkson traveled to Solzhenitsyn’s home in Vermont in 1987 for an interview and to record the author reading excerpts from his book. VOA sound engineer Robert “Bob” Louis Cole was in charge of the recordings. Bob Cole passed away in 2017. Courtesy Photo from VOA Russian Service 2017 video interview with Natalia Clarkson.

Ted Lipien was VOA acting associate director in charge of central news programs before his retirement in 2006. In the 1970s, he worked as a broadcaster in the VOA Polish Service and was a reporter and service chief in the 1980s during Solidarity’s struggle for democracy in Poland.

Notes:

- Ted Lipien, Interweaving of Public Diplomacy and U.S. International Broadcasting: A Historical Analysis,” American Diplomacy, December 2011, accessed November 10, 2017, http://www.unc.edu/depts/diplomat/item/2012/0106/ca/lipien_interweaving.html.

- Ted Lipien, “75th Anniversary of Voice of America – Propaganda Coordination with USSR,” Cold War Radio History Museum, January 17, 2017, accessed November 10, 2017, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/2017/01/17/75th-anniversary-of-voice-of-america-propaganda-coordination-with-ussr/.

- Ted Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, November 7, 2017, accessed November 9, 2017, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/2017/11/07/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/.

- Victor Franzusoff, Talking to the Russians (Santa Barbara: Fithian Press, 1998).

- Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation III-IV, 10.

- Aleksandr I. Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago 1918-1956: An Experiment in Literary Investigation I-II, 27.

- Ibid.

- Ted Lipien, “SOLZHENITSYN Target of KGB Propaganda and Censorship by Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, November 7, 2017, accessed November 10, 2017, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/2017/11/07/solzhenitsyn-target-of-kgb-propaganda-and-censorship-by-voice-of-america/.

- Mark Pomar, (Chief, Russian Service, USSR Division, Voice of America, August 1983 to July 1986, in discussion with the author, October 17, 2017.

- Natalie Clarkson, (Chief, Russian Branch, Voice of America, 1980s), in discussion with the author, October 18, 2017.

- Natalie Clarkson, (Chief, Russian Branch, Voice of America, 1980s), in discussion with the author, October 18, 2017.