New York, New York. 1943 “United Nations” exhibition of photographs presented by the United States Office of War Information (OWI) on Rockefeller Plaza. Listening to broadcasts of President Roosevelt, Churchill, Stalin, and Chiang Kai-shek, heard every half-hour from a loudspeaker at one end of the frame containing the Atlantic Charter. This frame is surrounded by four statues of the four freedoms. The Office of War Information was the U.S. government wartime propaganda agency in charge of early shortwave radio broadcasts later known as the Voice of America (VOA). Voice of America was not the official name of U.S. overseas radio broadcasts during World War II which were presented under several different names. The agency produced propaganda in various media for both foreign and domestic consumption, including propaganda films justifying the internment of Japanese American U.S. citizens. Wartime U.S. shortwave broadcasts covered up Stalin’s crimes and lauded the Soviet Union as supporting freedom and democracy. Some agency officials also engaged in illegal attempts to censor domestic U.S. media to prevent them from reporting negative news about the Soviet Union. In 1952, a report issued by a bipartisan congressional committee criticized U.S. government’s wartime propaganda activities, including Voice of America broadcasts, as misleading foreigners and Americans and harming longterm U.S. interests.

Support Cold War Radio Museum By Buying Our Books on Amazon

When the first U.S. government’s wartime direct radio broadcast in German had been transmitted to Europe from a studio in New York sometime in February 1942, these programs and the station in charge of their production were not yet known as the Voice of America (VOA). They would not be widely known under that name for several more years. We could find no official press release announcing the start of these broadcasts which later became part of a government-funded media outlet now called the Voice of America. VOA has been officially using this name and is recognized under this for many decades. Much of VOA’s early history, however, has never been well documented. It may have been deliberately distorted and partly erased from memory by U.S. government officials and friendly historians in an ultimately misguided effort to protect VOA’s image during the Cold War.

In the beginning, it was not at all clear what the U.S. government shortwave radio operations were officially called, but it was clear what they were to achieve — a propaganda advantage over Nazi Germany and Japan. Those in charge of early U.S. broadcasts were not worried about Soviet propaganda. Being strongly pro-Soviet, they considered it helpful to the U.S. war effort and allowed it to influence U.S. radio propaganda. They often incorporated Soviet propaganda, including its lies and disinformation, into U.S. broadcasts.

The early American programs for overseas audiences had various names, such as “Voices from America” and “America Calling Europe.” The “Voice of America” brand was not yet firmly established and early U.S. government propagandists strangely did not attempt to create a distinctive brand, most likely because they did not think that these programs would outlast the war. Some listeners to U.S. government shortwave radio broadcasts could not recall their exact name, but they remembered them for pushing Soviet propaganda.

With genuine horror we listened to what the Polish language programs of the Voice of America (or whatever name they had then), in which in line with what [the Soviet news agency] TASS was communicating, the Warsaw Uprising was being completely ignored. 1

In the first months of the war with Japan and Nazi Germany, the Roosevelt Administration issued a number of public warnings about Japanese and German propaganda attempting to to influence American public opinion. In articles reminiscent of some of the reporting on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election campaign, there were warnings from the Roosevelt Administration that German and Japanese propaganda broadcasts were designed to interfere with the American electoral process. A short news item in the U.S. government news bulletin Victory issued by the Office of Facts and Figures (OFF), on April 7, 1942 included such a warning under the title: “Axis radiocasters try to put their hooks into U.S. primary elections”:

In the first months of the war with Japan and Nazi Germany, the Roosevelt Administration issued a number of public warnings about Japanese and German propaganda attempting to to influence American public opinion. In articles reminiscent of some of the reporting on Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election campaign, there were warnings from the Roosevelt Administration that German and Japanese propaganda broadcasts were designed to interfere with the American electoral process. A short news item in the U.S. government news bulletin Victory issued by the Office of Facts and Figures (OFF), on April 7, 1942 included such a warning under the title: “Axis radiocasters try to put their hooks into U.S. primary elections”:

Axis radiocasters try to put their hooks into U.S. primary elections

Enemy propagandists jumped into American politics March 31, OFF revealed.

In the role of volunteer campaign orators, they took to the air in anticipation of the coming primary elections.

The Nazis beamed a new program at the United States from their so-called “American Freedom” station, with one Joe Scanlon, calming to be an American. he exhorted:

Join us in our endeavor to save our boys from foreign battle fields. You can compel the Government to act. The elections are coming again and our people will have a last opportunity to reassert themselves. Organize as free Americans to fight the dictatorship being set up in Washington. The only real enemies sit right within the ranks of our Government today.”

Tokyo’s “America First”

Tokyo named the new short-wave broadcast the “America First” program and the Japanese “America Firster” declared:

“The isolationists were right.”

From Tokyo too came the assurance that, “Japan would be a charming partner to any nation that would understand Japan’s ideals correctly,” and the promise that Japan would share with the United States its newly won rubber and tin if only Americans “will get rid of Roosevelt.” 2

While German and Japanese shortwave radio broadcasts had a very limited listenership in the United States, the fear of their impact was high. The Roosevelt Administration, however, was remarkably silent about its own efforts to counter such a threat or its plans to target Germany with American propaganda. It was also silent about Soviet and communist propaganda in the United States. The U.S. government launched radio broadcasts in many foreign languages during the war, but strangely and significantly there was no Russian-language radio program. VOA did not start broadcasting in Russian until 1947.

U.S. radio broadcasting during the war did not have an easily recognizable name or a separate director in charge of the combined news and radio operations. They were initially known as “Radio Program Bureau” in the Overseas Branch of the Office of War Information (OWI). Programs were written and recorded mostly in New York, where the overseas radio operation was based. The Radio Program Bureau had a chief, not a director, who reported to the Chief of the New York Regional Office and the Director of the Overseas Branch of the OWI. The Overseas Branch Director based in New York reported to the OWI Director in Washington.

The U.S. German radio program went on the air with the announcement Stimmen aus Amerika (“Voices from America”) sometime in February (various dates have been suggested), but the VOA name was not officially adopted for these overseas broadcasts until several years later. Initially managed by the U.S. government’s Office of the Coordinator of Information (COI) and distributed by its Foreign Information Service (FIS), these radio programs were managed after June 1942 by the newly-created Office of War Information, a central government propaganda agency targeting both domestic and foreign publics. They remained there until 1945 when the Office of War Information was abolished by an executive order signed by President Truman. Voice of America programs were then transferred to the State Department, but even then the State Department office in charge of the radio broadcasts did not have “Voice of America” in its official name although by then it was the name commonly used to describe them to radio listeners abroad and to American taxpayers who paid for them.

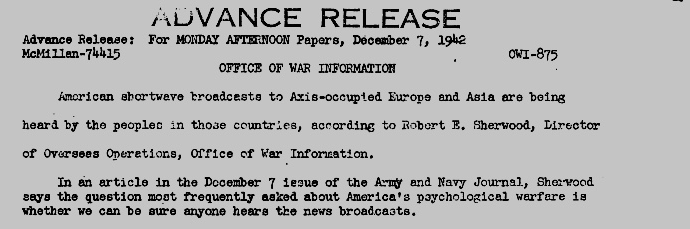

One of the first, if not the first U.S. government press release about World War II U.S. shortwave radio programs to Europe and Asia was issued on December 7, 1942 on the first anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It took about ten months after the first German radio broadcast went on the air for the Roosevelt Administration to explain to Americans in a government press release how it was responding to Nazi and Japanese propaganda. In the press release, Robert E. Sherwood, Director of Overseas Operations in the Office of War Information, used the phrase “voice of America” but not as the official name of these transmissions. “V” in “voice” is not capitalized, either in the press release or in the magazine article to which it referred. 3 Sherwood, a Hollywood playwright who also served as President Roosevelt’s speechwriter, described what everyone then agreed were propaganda and psychological warfare operations aimed against America’s enemies. They were also designed to support underground resistance in countries under Axis occupation, as Sherwood explained in more detail in his article titled “‘Send the Word, Send the Word–Over There’: The U. S. On the Psychological Warfare Front” published in The Army and Navy Journal.

###

Office of War Information Press Release – December 7, 1942

ADVANCE RELEASE

Advance Release: For MONDAY AFTERNOON Papers, December 7, 1942

McMillan-74415OWI-875

OFFICE OF WAR INFORMATION

American shortwave broadcasts to Axis-occupied Europe and Asia are being heard by the peoples in those countries, according to Robert E. Sherwood, Director of Overseas Operations, Office of War Information.

In an article in the December 7 issue of the Army and Navy Journal, Sherwood says the question most frequently asked about America’s psychological warfare is whether we can be sure anyone hears the news broadcasts.

Although no polls of opinion can be taken in these countries, Sherwood says, “We get the answer from our enemies themselves, from their increasing admonitions to their own people to stop believing the lies that are told them by American and British and Russian and Chinese propagandists. Our enemies wouldn’t be denying these ‘lies’ if their peoples in ever increasing numbers had not heard or read them.”

Increased access to the vast facilities of the British Broadcasting Company has helped make possible the distribution of American news in Europe, the article states.

“Several times each day the people of Europe can hear the voice of America rebroadcast by the powerful battery of B. B. C. transmitters, long wave as well as short wave.”

In addition to communicating with the peoples of occupied countries by broadcast, the Director of Overseas Operations emphasizes that word is gotten into Axis-dominated countries by every other available means.

Sherwood cites the “friendly and valuable cooperation with the R. A. F. Within a month after Pearl Harbor, the R.A.F. was dropping millions of American leaflets which gave the text of President Roosevelt’s first war-time report on the state of the Nation.”

This means of communications also was used simultaneously with Presidont Roosevelt’s address to the French people, broadcast from more than 50 transmitters on both sides of the Atlantic, to herald arrival of an A.E.F. in North Africa.

“Words can bolster the morale of our friends overseas and thus increase their powers of resistance. Words can disrupt the morale of our enemies and thus decrease their powers of resistance,” Sherwood says.

According to Sherwood, the most remarkable achievement in psychological warfare was that of the British in 1940-41. Their confidence in meeting the enemy, the words they hurled into Europe “confounded the all-conquering Nazis and sowed in their people the first seeds of doubt of their invincibility.

“The delivery of such great words to the peoples who must hear them has been the job of the various psychological warfare agencies of the United Nations.

“We have been sending the word over there by radio, by press services, by pamphlets, leaflets, posters, movies and even by word of mouth which travels with mysterious speed and effectiveness and penetrates the stoutest walls of censorship and suppression that the Nazis, the Fascists or the fanatical militarists of Tokyo can build about their own and conquered peoples.

“‘The Yanks are coming!’”

###

It it worth noting that when used with reference to World War II U.S. radio broadcasts, terms such as propaganda and psychological warfare did not yet have a strongly negative connotations that they do now. Many Americans, including some American journalists outside of the government, considered propaganda and psychological warfare broadcasts to be a normal and necessary part of fighting a total war. In his article, Sherwood explained the role of propaganda as assisting in the war effort but not a substitue for use of military force to defeat the enemy.

Words will not win this war. Words will not even win a little part of this war unless they are the convincing heralds of the overwhelming power of our armed forces and the unqualified good faith of our Government. But the right words delivered at the right place at the right time can save the lives of soldiers and sailors of the United Nations who have to do the real fighting and the real winning. 4

Early U.S. radio programs usually did not include outright lies, but they often intentionally did not offer the full truth and distorted it according to the wishes of the administration, and, even more often and more dangerously, according to strong ideological biases of their authors. This applied especially to news and commentary about the Soviet Union. Soviet Russia was then America’s major military ally against Nazi Germany. During the war, Russia was not criticized or exposed in U.S. government’s broadcasts for expansionist and repressive policies of its totalitarian communist regime. It was presented instead by the Roosevelt Administration, both to foreign audiences and to Americans, as a dynamic progressive nation and a valuable partner helping the United States to defeat Germany that would also help build a more peaceful world after the war. Those who knew better, including some members of Congress, were appalled by such pro-Soviet propaganda and warned that the United States government would come to regret it.

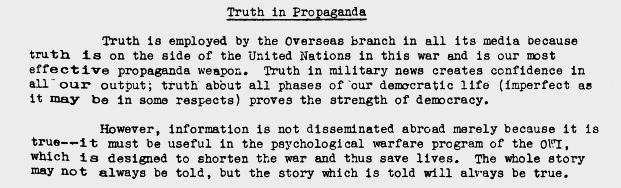

“The Manual of Information” for the News and Features Bureau in the Overseas Branch of the Office of War Information printed for internal use in February 1944 explained in some detail the purpose of OWI’s propaganda and psychological warfare programs.

It pointed out that President Roosevelt’s Executive Order “of June 13, 1942, and a later order of March 9, 1943, charged the Office of War Information with the responsibility of conveying information to the world at large and empowered it to conduct among foreign nations propaganda which would contribute to victory.”

The manual also noted that “the program for foreign propaganda in areas of actual or projected military operations was to be coordinated with military plans and subject to the approval of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.”

In the words of Elmer Davis, Director of the Office of War Information, at a hearing of the subcommittee of the Committee on Appropriations of the U.S. House of Representatives May 18, 1943:

“…this is a war agency, which owes its existence solely to the war, and was established to serve as one of the instruments by which the war will be won…an auxiliary to the armed forces whose effectiveness has been recognized by military commanders all the way down from Julius Caesar to George C. Marshall.” 5

While the manual emphasized the need for truth in military news, it also provided a significant loophole for censoring information considered harmful to the war effort. 6

Truth in Propaganda

Truth is employed by the Overseas Branch in all its media because truth is on the side of the United Nations in this war and is our most effective propaganda weapon. Truth in military news creates confidence in all our output; truth about all phases of our democratic life (imperfect as it may be in some respects) proves the strength of democracy.

However, information is not disseminated abroad merely because it is true–it must be useful in the psychological warfare program of the OWI, which is designed to shorten the war and thus save lives. The whole story may not always be told, but the story which is told will always be true. 7

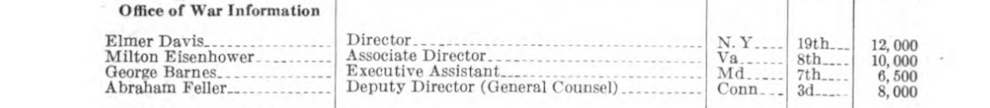

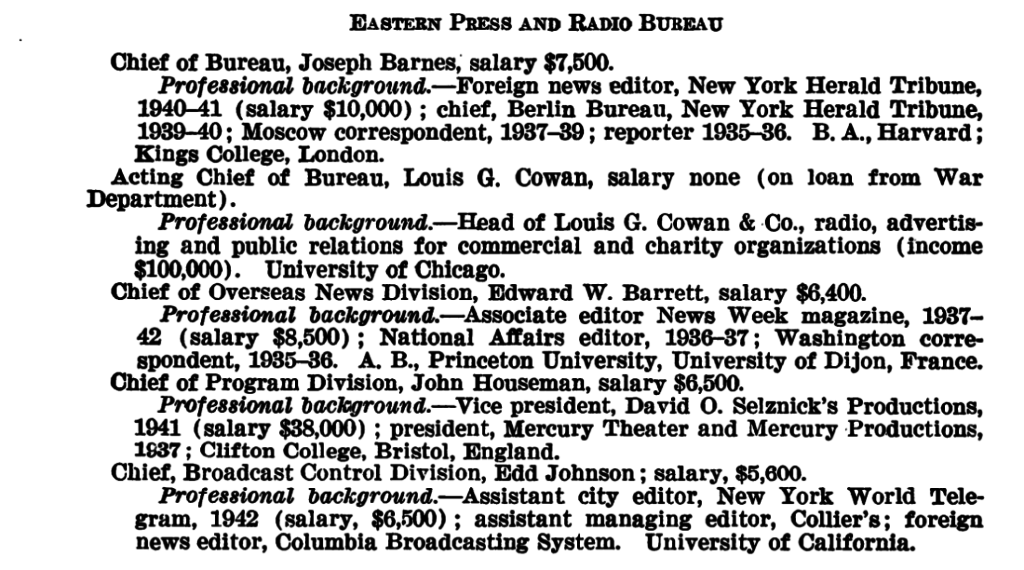

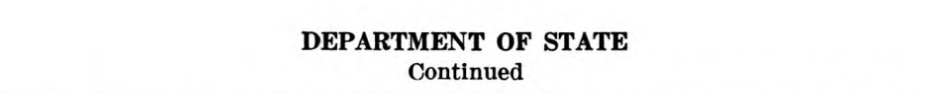

The U.S. government-hired staff preparing these early broadcasts included a number of communist and Soviet sympathizers. Some of them found government employment thanks to John Houseman, a theatre producer who was most directly in charge of radio production rather than in charge of editorial policy. His official title was not the Voice of America director. The 1943 Official Register of the United States listing persons occupying administrative and supervisory positions in the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the Federal Government, and in the District of Columbia Government, as of May 1, 1943, shows Houseman’s official title as: “Chief, Radio Program Bureau, Overseas Branch, Office of War Information.” Officials who were later in charge of the Voice of America and friendly historians assigned the title of the first VOA director to him several years later usually without mentioning that the organization was not created under that name. They also glossed over the fact that the early radio operation was controlled by extreme left-wing idealists and pro-Soviet sympathizers, with John Houseman being one of them, but not necessarily in the most important executive position.

…

…

…

…

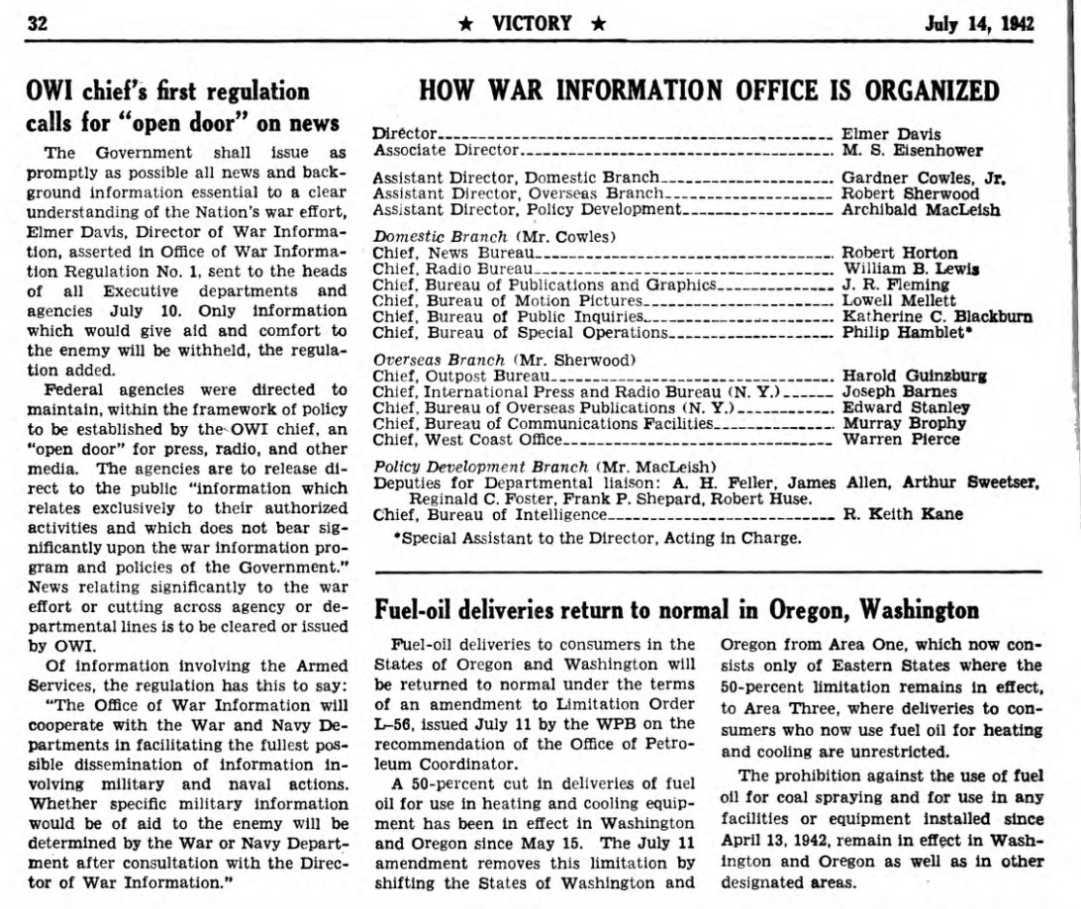

Another organizational list of the Office of War Information personnel was published on July 14, 1942 in Victory, the official weekly bulletin of the OWI. It shows Joseph Barnes as Chief, International Press and Radio Bureau (N.Y.). Barnes was John Houseman’s immediate boss. Houseman’s name does not appear on the personnel list in the Victory bulletin. One could only speculate that his was not one of the most important positions within the organization. 8

There was no specific information in the Office of Facts and Figures (OFF) and later OWI Victory weekly bulletins in 1942 about the start of U.S. government’s shortwave broadcasts to Europe. It went largely unnoticed.

In 1942, official U.S. government news bulletins had far more material on Nazi and Japanese propaganda broadcasts than about any American efforts to counter them abroad. A news item in the January 20, 1942 Victory bulletin published by the agencies in the Office for Emergency Management said that on January 16, Archibald MacLeish, director of the Office of Facts and Figures, announced designation of the radio division of the OFF, under William B. Lewis as coordinator, as the central clearing agency for governmental broadcasting. The announcement said that “The action was taken by direction of President Roosevelt in a letter from Stephen Early, Secretary to the President, to Mr. MacLeish, under whose supervision the letter directed that the work be done.”

The letter also mentioned that Mr. MacLeish, through Coordinator Lewis, was “to handle certain Government programs on the networks in the United States,” 9 thus setting the stage for distribution of U.S. government’s propaganda not only abroad but also domestically. Domestic U.S. government propaganda later became a major conflict point with many members of Congress and some of the ethnic communities in the United States which viewed Stalin and the Soviet Union with considerable suspicion.

References to U.S. shortwave broadcasting operations were also rare in later editions of OWI bulletins. A brief news item in Victory on November 10, 1942 mentioned leasing by the government of 10 short-wave stations from five American commercial companies for the duration of the war emergency.

Another news item on November 10, 1942 mentioned President Roosevelt’s November 7 “Vice La France Eternelle!” radio broadcast in French to the French people in connection with U.S. military operations in French North Africa but did not explain how it was broadcast and by by whom.

A December 8, 1942 report described a special shortwave radio program offering scholarship to Islandic students at eight universities in the United States, again without giving the name of the U.S. government broadcaster in the Office of War Information. The Voice of America as a separate entity was not yet named as such or widely recognized as a government-run news organization. Its main purpose was propaganda and psychological warfare in support of what was generally accepted as the right cause of resisting fascism and helping the war effort. Most Americans, with the exception of some members of Congress, did not know that some of these early U.S. government broadcasters were also working to help Stalin and the Soviet Union achieve post-war political goals and from time to time worked against the policies and the interests of the United States set by the Roosevelt Administration. Some would even risk the lives of American soldiers with propaganda broadcasts if they concluded that the White House, the State Department and the War Department failed to be sufficiently progressive and supportive of causes and factions favored by the Soviet Union.

In a transcript of hearings on the 1943 OWI budget held on September 28, 1942 before a subcommittee of the House of Representatives Committee on Appropriations, John Houseman’s name appears with the tile Chief of Program Division 10

In the 1944 Official Register of the United States, Elmer Davis is listed as the OWI Director, Robert Sherwood as Overseas Branch Director, Louis G. Cowan as Chief of New York Regional Office, and Lawrence Blochman as Chief of Radio Program Bureau. 11 In 1945, Edward W. Barrett is listed as Director of the Overseas Branch. Cowan and Blochman still have the same titles. 12

In 1946, after it was moved to the State Department, the Voice of America name still does not appear in the Official Register. John W. G. Ogilvie is listed as Acting Chief of the International Broadcasting Division in the State Department’s Office of International Information and Cultural Affairs. 13

Later editions of the Official Register until its last edition in 1959 also do not list the Voice of America as a separate administrative entity by that name within the State Department and in the United States Information Agency (USIA). However, after 1945 the Voice of America name is starting to appear in the Congressional Record and in other U.S. government and non-government publications. The 1946 edition of Broadcasting Stations of the World published by the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service of the U.S. War Department lists medium wave radio transmissions of “The Voice of America in North Africa” by U.S. Information Service. 14

In February 1946, Assistant Secretary of State William Bennett spoke at length about Voice of America broadcasts and used the name repeatedly while testifying before the House Appropriations Committee about the 1947 budget request for the State Department. 15

The 1948 Official Register of the United States shows U.S. international broadcasting as the State Department’s “Division of International Broadcasting, headed by Charles Thayer, a Foreign Service Officer. It is listed under the State Department’s “Office of International Information.”

1948

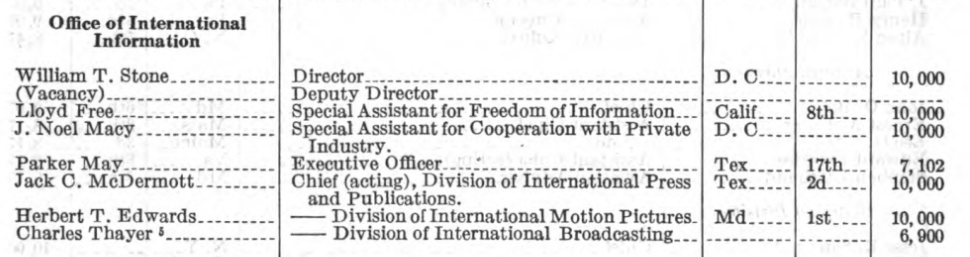

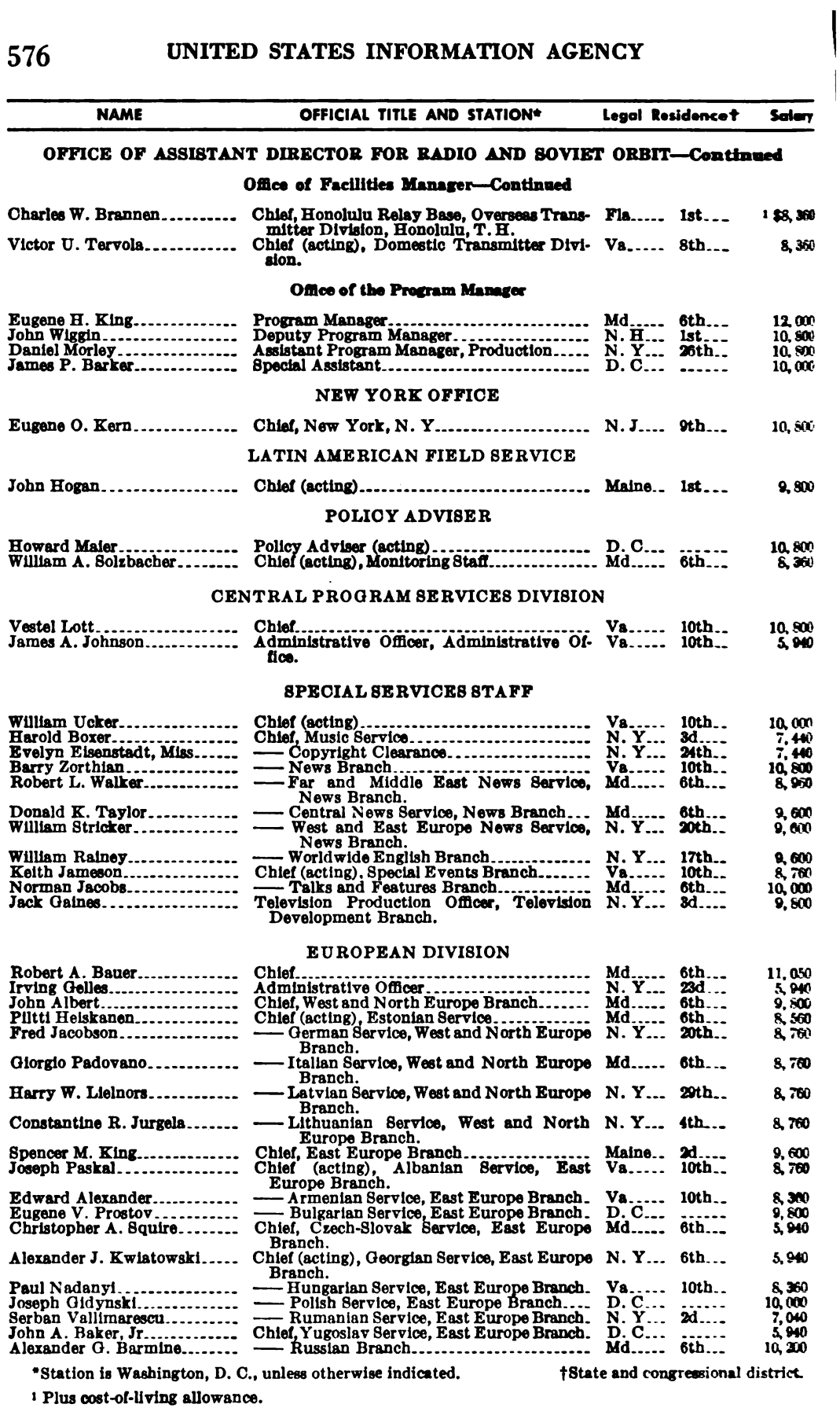

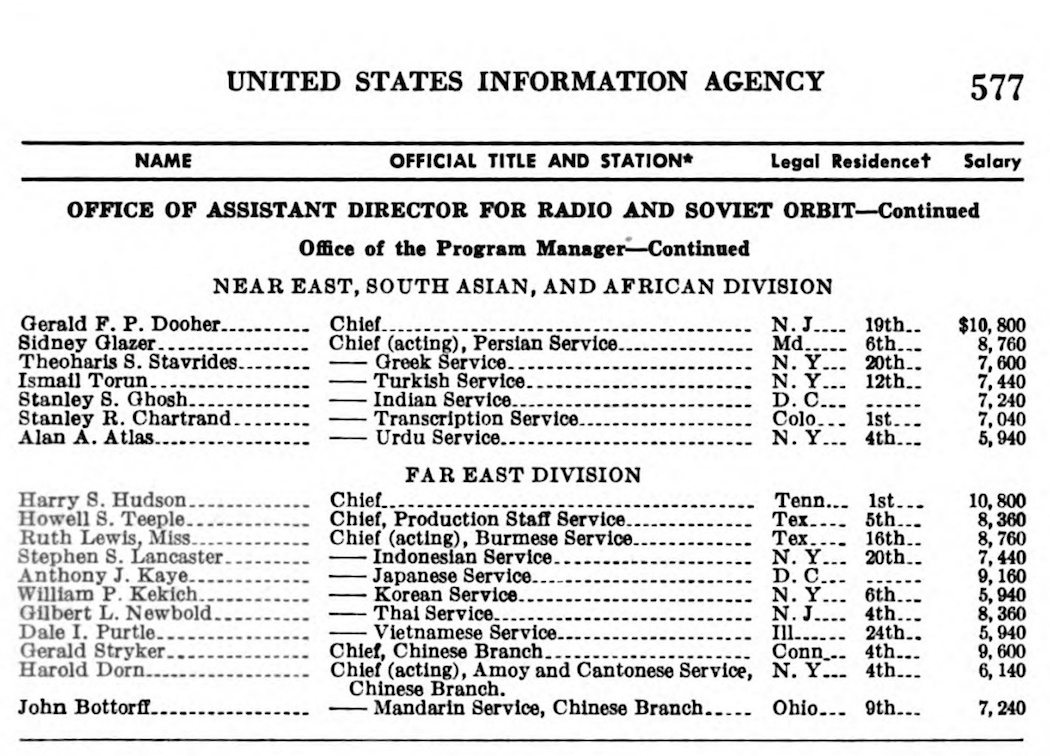

After the Voice of America was moved in 1953 from the State Department to the newly-created United States Information Agency (USIA), it was placed in the Office of “Assistant USIA Director for Radio and Soviet Orbit.”

1954-1955

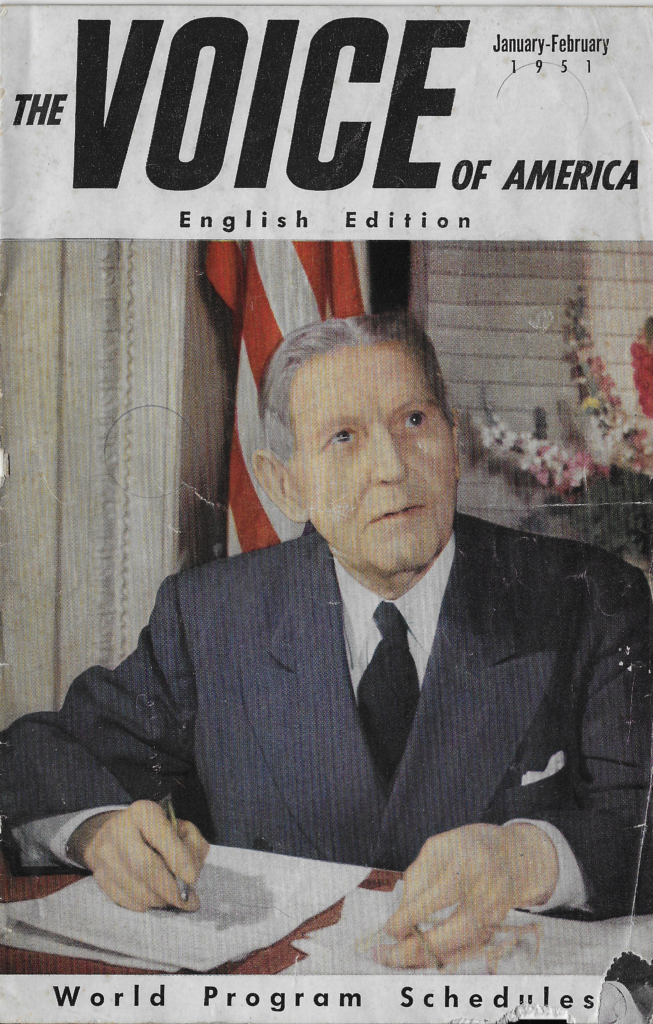

While the State Department and United States Information Agency offices where the Voice of America was placed and administered did not have VOA as their official name, Voice of America broadcasts and promotional materials issued in the 1950s regularly used the VOA brand name.

VOA 1951 Program Schedule Brochure

JANUARY – FEBRUARY 1959

The VOICE OF AMERICA Program Schedule is published by the United States Department of State, New York 19, N.Y., U.S.A. Send communications to this address

This publication appears simultaneously in English, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, Korean and Chinese. Except where indicated, the contents of this Schedule are not copyrighted and may be reproduced by newspapers or magazines.

VOA 1959 Program Schedule Brochure

Within 3 months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Voice of America went on the air for the first time to tell the truth about America’s participation in the second world war.

The first broadcast (on February 24, 1942) [Cold War Radio Museum: various dates in February 1942 have been mentioned for the airing of the first German-language broadcast] was in the German language, penetrating the censorship screen established by the Nazi leaders. At the height of the war, the Voice was broadcasting more than 3,200 live programs weekly in about 40 languages.

Today, the Voice of America, speaking for the U.S. Government as the radio service of the U.S. Information Agency, provides millions of listeners in many parts of the world with objective newscasts, up-to-the-minute facts about U.S. policies, and information concerning the life and culture of the American people. Its broadcasts are beamed around the clock and around the globe in 37 languages over a network of 76 transmitters.

VOA’s Erased History

The Voice of America was not initially designed to be primarily a news gathering and news reporting organization. Office of War Information Director Elmer Davis told House Appropriations Committee members in 1942 that the main focus of shortwave radio broadcasts was propaganda and psychological warfare operations in support of the war effort, but he added that there was both good and bad propaganda:

I repeat what I said about propaganda — that it is an instrument which may use truth or falsehood as its material, which may be directed toward worthy or unworthy ends. We are going to use the truth, and we are going to use it toward the end of winning the war; for we know what would happen to the American people if we lose it. “Propaganda” is a word in bad odor in this country, but there is no public hostility to the idea of education as such, and we regard this part of our job as education. If we do it wrong, there is an ever-present safe guard. We tell you the way it looks to us, and if it looks otherwise to somebody else, there is no law against his standing up and saying so — in Congress, or on the radio, or in the newspapers, or on a soapbox. 16

OWI Director Elmer Davis told members of Congress that “propaganda is an instrument.” He stressed that “to condemn the instrument, because the wrong people use it for the wrong purposes, is like condemning the automobile because criminals use it for a getaway.” 17

Davis would later promote in “Voice of America” and domestic U.S. government radio broadcasts the biggest Soviet propaganda fake news lie of the 20th century about the mass murder of thousands of Polish POW officers and intellectual leaders known collectively as the Katyn Forest Massacre. His agency also tried to censor independent U.S. media outlets which exposed Soviet crimes to Americans.

A bipartisan congressional committee concluded in 1952 that “Mr. Davis, therefore, bears the responsibility for accepting the Soviet propaganda version of the Katyn massacre without full investigation.” The committee added: “Testimony before this committee likewise proves that the Voice of America—successor to the Office of War Information—had failed to fully utilize available information concerning the Katyn massacre until the creation of this committee in 1951.” 18

In general, wartime U.S. government propaganda broadcasts presented Stalin as a trusted ally of the United States and a supporter of democracy and social justice. They also covered up his genocidal crimes and any truly negative news about communism. Early VOA broadcasters later backed the establishment of pro-Soviet governments in East-Central Europe in line with Moscow’s and, to only some extent, with FDR’s wishes. Their support for various communist movements and for the propaganda line from Moscow, however, often went beyond what even the FDR White House was willing to tolerate and produced conflicts with U.S. military leaders, including General Dwight Eisenhower. He accused those in charge of wartime Voice of America of “insubordination” toward the President of the United States. 19 After the war, a few of the early VOA journalists went to work for communist regimes in Eastern Europe.

As these early U.S. broadcasts took shape, some high-level officials within the Roosevelt Administration became concerned about the staffing of the radio broadcasting operation. In April 1943, the State Department informed the White House in a secret memo sent by Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles that John Houseman was too dangerously pro-Soviet even for the generally pro-Soviet American foreign policy at that time. Welles held the second top job in the State Department and was one of FDR’s close friends and foreign policy advisors. The State Department with the support of the Army Intelligence refused to issue Houseman a U.S. passport for official travel abroad. Houseman and several other early U.S. officials in charge of the broadcasting effort were forced to resign.

However, U.S. radio broadcasts favoring the Soviet Union continued through the end of World War II at the direction of Houseman’s patron, Robert E. Sherwood, who coordinated U.S. and Russian propaganda, first in Washington and later in London with the approval of the White House and the State Department but apparently with more enthusiasm than even the administration would have wished. Another of President Roosevelt’s personal friends and advisors, Adolf A. Berle who during the war was Assistant Secretary of State, wrote in his memoirs published in 1973 that World War II OWI and VOA officials were “following an extreme left-wing line in New York, without bothering to integrate their views with the State Department.” 20

The Voice of America did not immediately change its programming policy after the war. Even as the Cold War with the Soviet Union intensified, the change in VOA broadcasts was slow. A member of Congress read to the House of Representatives letters from Voice of America listeners in Poland describing some VOA radio programs in 1951 as “drab” and “unconvincing.”

VOA started to report more fully on Soviet atrocities in the early 1950s, mostly as a result of strong pressure from Congress. During World War II, there were no U.S. radio broadcasts in Russian as government officials in charge of what became the Voice of America did not see a need for them and were also most likely afraid that such broadcasts might offend Stalin and damage U.S.-Soviet friendship. This is also part of the erased or rarely mentioned early history of the Voice of America which later played a commendable role in winning the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

Support Cold War Radio Museum By Buying Our Books on Amazon

Notes:

- Straszewicz, Czesław. O Świcie. Kultura, October, 1953, 61-62.

- United States. Office of War Information, United States. Office for Emergency Management. Division of Information, and United States. Office for Emergency Management. Victory. Washington, D.C.: Division of Information, Office for Emergency Management, April 7, 1942, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112088069015?urlappend=%3Bseq=493. Accessed 04 June 2018.

- United States. Office of War Information. [Press Release] OWI-875, December 7, 1942.

- Robert E. Sherwood, ‘Send the Word, Send the Word–Over There” The U.S. On the Psychological Warfare Front. Army and Navy Journal, December 7, 1941 – December 7, 1942, 104.

- United States. Office of War Information. News and Features Bureau. Training Desk. Manual of Information, News And Features Bureau, Office of War Information, Overseas Branch. [Washington?]: The Training Desk, 1944.

- United States. Office of War Information. News and Features Bureau. Training Desk. Manual of Information, News And Features Bureau, Office of War Information, Overseas Branch. [Washington?]: The Training Desk, 1944.

- United States. Office of War Information. News and Features Bureau. Training Desk. Manual of Information, News And Features Bureau, Office of War Information, Overseas Branch. [Washington?]: The Training Desk, 1944.

- United States. Office of War Information, United States. Office for Emergency Management. Division of Information, and United States. Office for Emergency Management. Victory. Washington, D.C.: Division of Information, Office for Emergency Management, July 14, 1942, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015051143553;view=1up;seq=48. Accessed O4 June 2018.

- United States. Office of War Information, United States. Office for Emergency Management. Division of Information, and United States. Office for Emergency Management. Victory. Washington, D.C.: Division of Information, Office for Emergency Management, January 10, 1942, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uiug.30112088069015?urlappend=%3Bseq=114. Accessed 04 June 2018.

- United States. Congress. House. Hearings. Washington, D.C.: U.S. G.P.O., Hearings Cong. 77 sess. 2 Appropriations v. 15 1942, 406.

- United States Civil Service Commission. Official Register of the United States, 1944. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- United States Civil Service Commission. Official Register of the United States, 1945. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- United States Civil Service Commission. Official Register of the United States, 1946. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.

- United States. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. Broadcasting Stations of the World. Washington, D.C.: Foreign Broadcast Information Service, 1946.

- United States. Congress. House. Committee on Appropriations. Department of State Appropriation Bill for 1947: Hearings Before the Subcommittee of the Committee On Apropriations, House of Representatives, Seventy-ninth Congress, Second Session, On the Department of State Appropriation Bill for 1947. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1946.

- United States. Congress. House. Committee on Appropriations. Hearings: [National Defense] 1943 2nd supply. 387, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015035800377?urlappend=%3Bseq=389. Accessed 04 June 2018.

- Ibid. 385.

- The Katyn Forest Massacre. Final Report of the Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre pursuant to H. Res. 390 and H. Res. 539, Eighty-Second Congress, a resolution to authorize the investigation of the mass murder of Polish officers in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk, Russia, (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952), https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435078695582. Accessed 04 June 2018.

- [Footnote in “Waging Peace” by Dwight D. Eisenhower: “During World War II the Office of War Information had, on two occasions in foreign broadcasts, opposed actions of President Roosevelt; it ridiculed the temporary arrangement with Admiral Darlan in North Africa and that with Marshal Badoglio in Italy. President Roosevelt took prompt action to stop such insubordination.” Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279.

- Adolf E. Berle, Navigating the Rapids: 1918-1971, ed. Beatrice Bishop Berle (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovic, Inc., 1973), 440.

2 Comments

Dana Barish

Is it true that it is or was at one point illegal to publish VOA transcripts?

Curator

It was not illegal for media or private individuals to publish VOA transcripts if they managed to obtain them or transcribed them from radio broadcasts. It was, however, at one time illegal for VOA employees to publish such transcripts in the United States or to make them available to anyone other than media and members of Congress. This restriction was imposed by Congress out of legimitate fear that VOA’s government employees may try to influence U.S. domestic politics in partisan ways. The restriction was loosened a few years ago. Subsequently, there has been an increase in partisan reporting by VOA reaching American audiences. Such partisan reporting is still against U.S. law as it violates the VOA Charter.

Comments are closed.