OPINION AND ANALYSIS

By Ted Lipien

Note: The article has been updated to include information that Heda Margolius Kovály had worked in the 1970s as a freelance reporter for the Voice of America Czechoslovak Service under a radio name Kaca Kralova.

A declassified CIA report from 1953 featured a claim by a still unidentified Slovak source asserting that some Slovaks lost their lives and freedom because the U.S. government-run Voice of America (VOA) was broadcasting pro-communist propaganda and continued to downplay Stalinist crimes in radio programs to Czechoslovakia even into the early 1950s despite the drastic change of U.S. policy toward Moscow at the start of the Cold War. Another CIA source said in 1952 that “The greater the number of people listening to VOA, the greater the responsibility of those making these broadcasts.”

A declassified CIA report from 1953 featured a claim by a still unidentified Slovak source asserting that some Slovaks lost their lives and freedom because the U.S. government-run Voice of America (VOA) was broadcasting pro-communist propaganda and continued to downplay Stalinist crimes in radio programs to Czechoslovakia even into the early 1950s despite the drastic change of U.S. policy toward Moscow at the start of the Cold War. Another CIA source said in 1952 that “The greater the number of people listening to VOA, the greater the responsibility of those making these broadcasts.”

“A great deal of harm can be done by irresponsible broadcasting,” the CIA source warned.

Other sources said that Western broadcasts, particularly those by Radio Free Europe (RFE) and the BBC, had enough warnings of the regime’s atrocities being perpetrated even against Communist Party members, but they observed that at least in the early phases of the Cold War, committed Communists in Czechoslovakia were not regular listeners to these American and British radio programs.

According to accounts from two persons, one of them, an unidentified CIA source, and another, the wife of a communist regime technocrat who became a victim of the Stalinist trials, in the period shortly after World War II a small group of dedicated communists in government positions in Czechoslovakia had refused to believe in Stalin’s crimes and initially dismissed Western radio reports about communist terror, regarding such broadcasts as subversive work of imperialist propaganda. Later, some of them paid with their lives for their outright rejection of outside sources of information, but confirmation bias among those blinded by ideology, partisanship and propaganda was just as strong then, if not stronger, than it is today.

There is also the question of whether more non-Communists and Communists could have received a better warning and perhaps been able to save their lives if the U.S. government-run Voice of America prior to the creation in 1950 of also U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe, instead of supporting the consolidation of communist regimes in Eastern Europe, adequately presented all available evidence of Stalinist crimes in the Soviet Union and elsewhere and had done it without triggering popular uprisings, which at that time would have been both bloody and pointless because of the massive presence of Soviet troops in East Central Europe and Moscow’s willingness to use them.

Getting answers to these questions is not easy. One source who was presumably a well-informed Slovak told the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in 1953 that as a result of U.S. policies and VOA broadcasts shortly after World War II, “many Slovaks paid with their lives or freedom” because of the Yalta Agreement and because they did not receive accurate information from VOA about the danger of returning from the West to communist-ruled Czechoslovakia. The same source also said that even when the U.S. government drastically changed its policy toward Moscow and the Soviet Block a few years after the war, “this new policy has not been reflected in VOA broadcasts to Czechoslovakia.” 1 Some of the early VOA broadcasters set an example by returning after the war to Czechoslovakia, where they joined or supported the Communist Party. They were, however, far from the only ones to have been deceived by Soviet propaganda which had presented anyone opposed to Stalin as a right-wing, pro-Nazi, imperialist reactionary and enemy of the working class. It was a failure on the part of many intellectuals and journalists on both sides of the Iron Curtain.

In the later years of the Cold War, the reformed Voice of America played a major role in breaking down the communist monopoly on information, but the organization’s early history presented on VOA’s official website is full of inaccuracies and misleading information. VOA still maintains that “The Voice of America began broadcasting in 1942 to combat Nazi propaganda with accurate and unbiased news and information” and that “Ever since then, VOA has served the world with a consistent message of truth, hope and inspiration.” 2 For most of VOA’s existence, the statement is true, but at times, especially during the early years, some VOA officials and broadcasters were stretching the truth and even lying because of their ideological bias and unwillingness to accept facts which contradicted their worldview. At various times, VOA censored reports about Stalin’s orders to murder thousands of WWII Polish military officers in the so-called Katyn Massacre and, as late as the 1970s, limited readings about Stalinist crimes from Alexandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago.

Getting a more accurate picture of the role of U.S. government-run radio broadcasting during World War II and for a few years after the war requires analyzing primary sources, including contemporary accounts by early listeners to VOA programs, formerly classified State Department and CIA memoranda, and remarks by members of the U.S. Congress reprinted in the Congressional Record, some of which were used for this article. As early as 1943, slightly over a year after Voice of America programs went on the air, President Roosevelt’s White House received a warning from a high-level State Department official, supported by the U.S. Army Intelligence, that VOA’s first pro-Soviet director, a theatre producer and later Hollywood actor John Houseman, was hiring his communist friends to work on U.S. radio broadcasts to Europe. The memorandum written by FDR’s personal friend and advisor, Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles, remained classified for several decades.

Blinded by Communist Propaganda

The April 1973 photo shows Heda Margolius Kovály signing copies of “The Victors and The Vanquished,” the first edition published by Horizon Press. The book was published in two sections, the first by Margolius Kovály, the second by Erazim Kohak. Following this edition, her memoir was published on its own several times, finally with the title “Under A Cruel Star.” Photo: Courtesy Margolius Family Archive.

[wiki]Heda Margolius Kovály[/wiki] (1919 – 2010), who recounted in books and interviews how a dismissal of even most obvious facts by committed Communists happened nearly 50 years ago without initially an effective challenge from Western journalism, was a low-ranking member of the Communist Party in post-World War II Czechoslovakia. She was the wife and later widow of [wiki]Rudolf Margolius[/wiki] (1913 – 1952), Czechoslovak Deputy Minister for Foreign Trade (1949–1952) in the Soviet-dominated regime. Her husband later became the youngest communist co-defendant in the infamous 1952 Rudolf [wiki]Slánský trial[/wiki] and lost his life. She would eventually become a freelance contributor to Voice of America radio programs to Czechoslovakia after emigrating to the United States. Her VOA radio name in the 1970s was Kaca Kralova.

While able to notice some of the early troubling signs of the failures of the communist economy in the late 1940s, Margolius Kovály freely admitted, after her escape from Czechoslovakia following the Soviet-led invasion of the country in 1968, to being generally blinded by communist propaganda along with her husband and other Communists in the years immediately after the end of World War II. In her memoir, Under a Cruel Star Publisher: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 3 published in the West, Heda Margolius Kovály made several comments about Western radio broadcasting during the early years of the Cold War.

According to her, Communist Party members like her first husband and their spouses were not among regular listeners to such broadcasts because they thought, at least initially, that Western radios spread nothing but lies about communism.

“It seems beyond belief that in Czechoslovakia after the Communist coup in 1948, people were once again beaten and tortured by the police, that prison camps existed and we did not know, and that if anyone had told us the truth we would have refused to believe it.” 4

At some point, the couple may have seen the writing on the wall, but according to Margolius Kovály‘s memoir, at first they did not believe in what Western broadcasters were reporting about human rights abuses being committed by the regime they supported.

“When these facts were discussed on foreign broadcasts, over Radio Free Europe or the BBC,” she wrote years later, “we thought it only more proof of the way the ‘imperialists’ lied about us.” 5

She admitted that it was not until the 1950s that she started to comprehend the true nature of Stalinism. Margolius Kovály wrote in her book that the final awakening to the grim reality of life under Soviet-imposed communism came only several years after the war after she had experienced communist repression in her own life.

“It took the full impact of the Stalinist terror of the 1950s to open our eyes.” 6

An Anti-Semitic Party Purge

Despite his relatively low-level government position, her husband, Rudolf Margolius, was arrested in 1952 and tortured to force him into making a preposterously false confession to preposterously false charges leveled against him at his political trial. Accused of participating in a “Trotskyite-Titoite-Zionist” conspiracy against the communist state, he received a death sentence on November 27, 1952 and was hanged by the Czechoslovak communist regime on December 3, 1952 along with ten other more senior party members. A former inmate in Nazi concentration camps who barely survived the Holocaust, married to another Holocaust survivor, he was only 39 years old at the time of his execution. Three of the defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment. Of the fourteen Czechoslovak communists sentenced in the Slánský trial for alleged anti-state crimes, eleven were Jews. Heda Margolius Kovály recalled that announcers of the regime-controlled Radio Prague were playing up the fact that most of the defendants were, as they put it, “of Jewish origin” even though earlier the communist doctrine only emphasized and promoted class, religious, ideological and, in some cases, ethnic hatred.

Heda Margolius was not arrested with her husband, which was the usual fate of spouses of Soviet leaders killed during Stalin’s reign of terror in the Soviet Union in the 1930s. In this respect, Czechoslovakia after the war was slightly different from Russia under Stalin. She herself never held any government positions and worked as a graphic artist for a state company. Following her husband’s execution, she became a freelance translator. After she had been abruptly fired from her regular job, she could only get menial paid work in Czechoslovakia, and even that with much difficulty. While falling seriously ill and being unable to move on her own during her husband’s trial, she was forcefully discharged from a hospital in Prague on the orders of the communist party and later suffered many other indignities as a single working mother in a communist state.

She and her husband were not communists before the war. As survivors of the Holocaust, they only joined the party after the war’s end, as she explained, in a mistaken belief that communism could help to eliminate ethnic hate and create a tolerant society. Over time, even without the benefit of Western broadcasts, to which she, by her own account, had not listened regularly, she developed doubts about the Stalinist system based on her own observation of everyday life of ordinary people and tried to persuade her husband to resign from his government job, although not from the Communist Party. He also apparently started to have his own doubts, but for him they turned out to be too late. In 1952, he became one of the victims of the Stalin-inspired anti-Semitic party purge in Czechoslovakia, not because he did anything to betray the party or the communist regime but largely because he was Jewish and happened to be responsible for negotiating a trade deal with Great Britain. Stalin did not want satellite countries to become more independent like Tito’s Yugoslavia and to develop economic relations with the West. In a fascist-like fashion, Stalin and his communist supporters in Czechoslovakia had used anti-Semitism to instill fear among party members and the population while at the same time trying to benefit from widely-held anti-Semitic prejudices. The Soviets found many local communist collaborators willing to carry out their plans.

The Slánský trial, while orchestrated in Moscow by Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, was executed with the help of some of the top Czechoslovak communist leaders and the local secret police. [wiki]Rudolf Slánský[/wiki] was in many ways different from Rudolf Margolius. Slánský was a Czechoslovak communist long before the war and became a senior member of the ruling establishment in post-war Czechoslovakia. He was a hardliner whom Rudolf Margolius, according to his wife, intensely disliked and avoided. He was also a propagandist. While living in exile in the Soviet Union during World War II, Slánský prepared broadcasts to Czechoslovakia over Radio Moscow. After the war he became the Czechoslovak Communist Party’s General Secretary, a position second only to the party chairman [wiki]Klement Gottwald[/wiki], and had a leading role in organizing communist rule though the illegal [wiki]1948 Czechoslovak coup d’état[/wiki]. Both Slánský and Margolius were, however, among those arrested in 1951 and 1952 on trumped-up charges of being supporters of anti-Stalin Yugoslav communist leader [wiki]Josip Broz Tito[/wiki], Western spies, and Zionists. Slánský was the chief defendant. He and most of the other executed Czechoslovak Communist Party officials convicted on the basis of fabricated evidence and false confessions extracted under torture were Jewish, as were Rudolf Margolius and his wife. The Slánský trial had very strong anti-Semitic overtones.

While Rudolf Slánský was a senior communist leader, himself responsible for some of the earlier atrocities against non-communists, Rudolf Margolius was not a member of the top leadership and had nothing to do with the earlier repressive measures. He was a deputy minister, an economist and a technocrat. Being Jewish and linked with foreign trade with the West made him, however, an easy target for Stalinist hardliners in the Czechoslovak regime and their Soviet patrons who were calling the shots. He may have been able to save himself if he had somehow managed to resign from his government position sufficiently early even if he could not withdraw from the party without reprisals, but apparently he did not have enough information and did not know that his life was endangered.

After her husband was arrested, Heda Margolius quickly realized that what Western radios had been saying were not lies. It was, however, too late to save her husband. She lost her privileged position as a wife of a communist official. Soon after her husband’s arrest, she was expelled from the communist party, lost her job, was forced to move out of their comfortable state-assigned apartment in Prague, and reduced to living in squalor. For years, she was unable to find steady employment using her professional skills and could only do freelance and menial work, which was often not enough to support herself and her young son. She lost her husband, her health and an opportunity for a decent life in communist-ruled Czechoslovakia.

Isolation from the West

The trauma of World War II, Nazism and the Holocaust, the Yalta Agreement, the overbearing presence of the Soviet Army, the willingness of some democratic Czechoslovak politicians to try to reach an accommodation and appease Moscow and local Communists, repression, propaganda and censorship by the communist regime, the initial failure of Western journalism, and the early pro-Soviet propaganda from the Voice of America before the station changed its course may have all contributed to the general confusion over Communism and Stalin’s political aims. Even if VOA broadcasts had not tried initially to hide Stalin’s crimes in the Soviet Union, it seems that both by circumstances beyond their control and in some cases also by choice, senior communist officials in Czechoslovakia and in other Soviet-dominated countries were for the most part isolated from the West and from Western sources of information until at least the early 1950s.

The son of Rudolf and Heda Margolius, Ivan Margolius, an architect and writer who since the 1960s has lived in Great Britain, told Prague Radio in a 2017 interview that his parents and other Czechs who had found themselves after the war in a similar situation as theirs, were cut off from the outside world. As Jews, they were also profoundly affected by the Holocaust, which, as he pointed out, may explain their initial support for Communism.

So, after the war, the impact of all of those horrors made him realize that he should do something to make the world better, and obviously the people who were incarcerated in the camps and in ghettos had lost contact with what was happening in the world. They had no information on what was happening politically elsewhere, so when they came out after the war, they didn’t have time to absorb the past six years of the war, in turn resulting in them being blinded by their experience and gave them this vision that they have to make the world better so that wars would never return and so that injustice towards minorities in the camps and the ghettos by the Nazis would never develop again, so that’s why he got involved with the government at the time, although it was a minor role; in the end being a deputy minister of foreign trade. [Read and listen to Radio Praha interview with Ivan Margolius, “‘Hitler, Stalin and I’ — An Oral History Based on Heda Margolius Kovály‘s Interviews with Czech Filmaker Helena Treštíková — Published in English.”]

As deputy minister for foreign trade, Rudolf Margolius made two official trips to Great Britain to negotiate a trade deal and was therefore not completely cut off from the Western world and alternative sources of information. It was, however, apparently not enough for him to break loose. Communist officials traveling abroad were closely watched. If he had defected in Britain, he would have been separated from his wife and she would be most likely arrested. There was no evidence that he had contemplated asking for political asylum. In the end, his official trip to the West, although approved by his superiors, may have become a major factor in his later arrest by the communist regime.

Holocaust and Communist Genocide

Both Heda Margolius Kovály and her first husband were among the few Czech-Jewish survivors of the Holocaust. The horrific experience of seeing your closest family members being marched to the gas chambers was how she explained their initial decision to join the Communist Party after the war despite some reservations. As an economist, her husband initially thought that socialism and communism would guarantee prosperity for Czechoslovakia and any other communist-ruled nation. They also naively thought that the triumph of socialism and communism would put a final end to anti-Semitism, racism and poverty. Both of her parents were murdered by the Nazis at Auschwitz while she herself was selected to be worked to death or killed later. Her husband was also a former Nazi concentration camp prisoner.

They seemed unaware that, like Hitler, Stalin also had been responsible for the murder by execution or starvation of millions of innocent people in the Soviet Union. Other Czech communists who had spent the war in the USSR and saw the crimes of the Soviet regime refused to share this knowledge after they returned to Czechoslovakia. If they did share such information and were denounced, they would have been promptly jailed and convicted of being traitors and enemies of the state.

Margolius Kovály wrote in her book that both she and her first husband eventually became disillusioned with communist rule, but they remained party members until their expulsion shortly after Rudolf Margolius’ arrest in 1952. Despite earlier doubts and warnings from friends, her husband refused to resign from his high-level position in the Ministry for Foreign Trade. In response to her pleas, he once had asked to be transferred from his government job, but the party rejected his request. He apparently did not seriously contemplate giving up his party membership. If he had, that in itself could have become a basis for being disgraced, losing his privileged status and possibly being arrested.

After the show trials in the Soviet Union in the 1930s, it should have been obvious to communists who had gained power in Eastern Europe with the help of the Red Army that none of them was safe, but many still refused to accept such facts and chose to believe instead, as Heda Margolius Kovály pointed out, that those accused by the party had been in fact guilty of their alleged crimes.

Such ignorance is difficult to understand. However, most Western and Czechoslovak journalists failed to report with sufficient detail on the enormity of the earlier genocidal crimes in the Soviet Union under Stalin. During World War II and for a few years afterwards, the Voice of America protected Stalin by covering up the truth about his crimes. The later excuse of VOA officials and journalists was that they did not know and could not have discovered the truth, but quite a few Roosevelt administration officials did know the facts and hid them from Americans and foreign audiences to protect the military alliance with the Soviet Union during the war, or did it out of their ideological sympathies, or both. Not all Americans, however, were deceived by propaganda. Both before and during World War II, some independent journalists and several members of the U.S. Congress were trying to expose Stalin’s genocidal crimes and questioned the necessity and value of concessions being made to appease the Soviet dictator.

Jamming of Radio Free Europe and Voice of America in Czechoslovakia

While it is not safe to make general observations on the basis of one personal account, Margolius Kovály and her husband were probably typical examples of idealistic and dedicated communists who initially refused to accept the evidence of the regime’s human rights abuses and made little effort to listen to Western broadcasts. Such a dismissive attitude may not have been true, however, of the rest of the population in Czechoslovakia, especially not for the regime’s early democratic opponents and non-communist victims of the regime who had relied on Radio Free Europe, the BBC and later the reformed and more assertive Voice of America for uncensored information and moral support.

Margolius Kovály was not completely unfamiliar with Western broadcasting. In her memoir she notes that she had listened earlier to the BBC programs in Czech during the war after her escape from a Nazi labor camp transport and her return to Prague, at that time still under German occupation. Presumably, she found the earlier BBC broadcasts during the war sufficiently credible and useful. She also recounted how most of her old friends among Czechs, who feared being shot by the Germans for helping an escaped Jew, had refused to give her shelter. 7

In another passage in her book, Heda Margolius Kovály suggests that after the communist coup in Czechoslovakia in 1948, listening to Radio Free Europe and other Western radio stations may have been nearly impossible due to the intentional jamming of their radio signals by the regime’s jamming transmitters. Other contemporary accounts also discuss intentional jamming, but most writers indicate that despite difficulties they were able to listen to such broadcasts, especially outside of the big cities. As the wife of a busy communist government official who worked long hours at the ministry, she apparently spent most of her time in Prague.

Very few people listened to foreign broadcasts such as Radio Free Europe or the BBC, partly out of fear, but mainly because the broadcasts were so effectively jammed that it was almost impossible to understand what was being said. 8

Committed Communists Refused to Believe

The first Radio Free Europe radio broadcast on July 4, 1950 was to Czechoslovakia under the name “the Voice of Free Czechoslovakia.” At that time, the Voice of America was still both unwilling and unable to counter Soviet propaganda with regular and effective programs specifically designed to expose communist crimes. Heda Margolius Kovály was probably right that in the beginning of communist rule over Eastern Europe, getting accurate information, even for those who sought it out, was not easy. It was, however, not completely impossible.

While ordinary people found valuable information and moral support in Western broadcasts, this is not how Heda Margolius Kovály described attitudes toward RFE and the BBC among communists in Czechoslovakia shortly after the war. While listening to Western radio stations in private homes among family members was fairly safe, many people were still afraid of being caught and imprisoned for either listening or repeating of what they had heard. This may have been especially true among Czechoslovak communists who were blinded by ideology and propaganda from their own party propagandists, journalists and broadcasters. All of them also had much more to lose as members of the privileged elite. Margolius Kovály initially seems to had underestimated the opposition to communism among ordinary Czechs and Slovaks, but in her book she honestly describes her own and her first husband’s wrong beliefs and mistakes. She may have also underestimated the ability of ordinary Czechs and Slovaks to tune in to Western shortwave radio broadcasts in spite of jamming.

It was true, however, that opponents of the regime would have been too fearful to share their real opinions with a party member and the wife of a high-level communist official. Getting accurate information, particularly during the early years of the Cold War, was not an easy task behind the Iron Curtain.

“Occasionally someone would catch a few words out of context, surmise the rest, and pass it on. That first bit became further distorted by repetition until people dismissed it with a wave of the hand, ‘Now you see how they lie!’” 9

A CIA View

American-funded Radio Free Europe ([wiki]Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty[/wiki]) was explaining much better than VOA in various languages what was actually happening in communist-ruled nations, but the early transmitters used in West Germany to broadcast such programs were weak and subject to intentional jamming of radio signals by communist regimes.

A report prepared in 1952 by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which then under a veil of secrecy was managing Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty, stated that “VOA’s one competitor is Radio Free Europe, which is regarded by the Czechs almost as their own station; RFE seems to understand the difficult life in the CSR and the desperation and hopes of the people. If RFE could overcome some technical difficulties, it would lead VOA by a wide margin…” 10 The same source in the now declassified CIA report said in 1952 that “Listening to Voice of America broadcasts in Czechoslovakia today is truly nation-wide; about 70-80 per cent of the adult population listens regularly to at least two programs a week.” 11

At that time, the Voice of America, the official radio station of the U.S. government, still largely refrained for various reasons from directly criticizing communism and consistently exposing Stalin’s crimes. However, personal observations, the word of mouth stories and improved power of U.S. broadcasts combined with the BBC’s broadcasting to Czechoslovakia should have provided over time a sufficient warning about communist atrocities to anyone willing to open their eyes. The 1952 CIA report said that “The quality of VOA reception on the whole can be described as good.” 12

According to Margolius Kovály, however, many communist bureaucrats in the early years of communist-ruled Czechoslovakia apparently refused to listen to Western radios out of a combination of loyalty to the party, ideological blindness, isolation and fear. This changed later in the Cold War when such listenership in the entire Soviet Block became nearly universal, but if one is to accept her observations as accurate, the ideological enthusiasm of early Czechoslovak communists combined with fear prevented some communist functionaries from seeking out alternative sources of information.

The 1952 CIA report tends to confirm her observations while making a distinction between listening habits of hardline communists as opposed to those of the rest of the population.

Generally, the great majority of the Czech people like most of the VOA programs quite well. They look eagerly to VOA as a source of information on the free world, a ready reporter of world news, defender and promoter of American interests and the American way of life, and the interpreter of American opinion on the activities of the Communists in that part of the world behind the Iron Curtain. There are only two small groups in Czechoslovakia that do not listen to foreign broadcasts; the “hard core” Communist Party members, and the small group of over-intellectualized individuals, who hate Communism but have no faith in Western democracy. The latter group is very dangerous; checking its growth depends on the effectiveness of VOA and other foreign broadcasts. 13

Otherwise, a CIA source presented a picture of widespread listening to Western radio broadcasts while pointing out some of the deficiencies in Voice of America programs in Western attitudes toward Czechoslovakia.

The programs beamed to Czechoslovakia prove that VOA has much good, factual material about the CSR. But one gets the impression that VOA does not have up-to-date information concerning the people, ie, their state of mind after three years of communist propaganda and mental pressure. This lack of understanding seems to me to be the major cause of difference in the reaction of listeners to RFE and VOA. This lack of understanding on the part of VOA might be caused by isolation or by insufficient contact. In this respect, RFE, has a tremendous advantage in having its headquarters close to the Czech border; it is able to establish direct contact with refugees, can “eavesdrop at the Iron Curtain.” It appears to me that VOA, located on a distant continent, either does not get enough intelligence reports about the people of Czechoslovakia, or such reports reach VOA through such complicated channels that they arrive too late to give an up-to-date picture. 14

Polish Communist Defector Reveals Regime’s Brutality in RFE and VOA Broadcasts

As late as 1951, the Voice of America, which was at that time located in New York but managed from Washington by the State Department, while usually less jammed than RFE, was under heavily criticism in the United States, particularly from Republicans in the U.S. Congress, for failing to counter Soviet propaganda. Voice of America listeners in communist ruled Poland, in letters smuggled to the United States described VOA programs as “uninteresting, drab, bureaucratic in tone, unconvincing.”

“They give the impression that they are prepared and spoken by clerks who do their job perfunctorily without any intelligent understanding of the human element or of Polish susceptibilities,” was one of many critical comments. Congressman Richard B. Wigglesworth (R-MA) read to the House of Representatives on July 24, 1951 highly critical comments on Voice of America broadcasts to Poland which, he said, had been “collected from letters and other messages by Polish writers and newspapermen” and brought to the United States by recent refugees. Management reforms carried out at VOA after such criticism resulted in making VOA programs to Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union more focused on events behind the Iron Curtain, more hard-hitting and ultimately more effective, but not nearly as effective as Radio Free Europe which continued to expose in much greater detail the corruption, crimes and failures of communist regimes.

There is ample evidence that after the Slánský show trial, many more Communist Party members started to tune in to Western radio broadcasts. As Radio Free Europe named communist informers and secret police officials who tortured political prisoners, communist apparatchiks and secret police members had additional reasons for paying attention to what their friends and neighbors may have been learning about them even while the regime tried to jam these radio transmissions to make listening difficult. Details of communist secret policy brutality, including accounts about disgraced and imprisoned communist leaders being tortured, were exposed in Radio Free Europe and Voice of America broadcasts by Polish defector [wiki]Józef Światło[/wiki], a former high-level member of the secret police. Interviews with Światło were used in RFE, Radio Liberty, and VOA programs to other countries, including Czechoslovakia, opening the eyes of many communist apparatchiks and making them realize that even they were not safe from the whims of their communist comrades and the feared secret police.

High-level Czechoslovak officials and party leaders in other Warsaw Pact countries were later provided in some cases with regime-prepared transcripts of Radio Free Europe, Voice of America, BBC, and other Western media broadcasts and newspaper articles about them and the situation in the Soviet Block nations. All evidence seems to indicate that Western radio broadcasting in local languages had a powerful impact not only on the general population but eventually also on the regime elites although Margolius Kovály seems to suggest that at least in the early years of communism in Czechoslovakia, Western radios’ influence among higher-level officials was small because they refused to listen and to believe in the veracity of what Western broadcasters were saying. They were blinded by their own propaganda. In the end, it were the non-communists who over time had forced a peaceful regime change in Czechoslovakia and in other Warsaw Pact countries in East Central Europe although some former disenchanted communists had joined the ranks of the opposition in later years of the Cold War.

Primary Victims of Communism were Non-Communists

Ironically, industrial workers were the first to rebel openly against communism in large numbers in some of the other Warsaw Pact countries, particularly in Poland in 1956, 1970, 1976, and 1980. They were avid listeners to Western radios. It is important to note in this context that communists represented only a tiny portion of the victims of post-war political terror in Czechoslovakia and in other countries, the point also made by Heda Margolius Kovály in her memoir. The Czechoslovak regime imprisoned and tortured thousands of its democratic opponents, ethnic Czechs, Slovaks, Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Jews and anybody else suspected correctly or incorrectly of being an enemy. Ordinary citizens also experienced much earlier than the communist elite what it meant to live under communist lawlessness and communist economy. In her book, Margolius Kovály described her own early observations of how the Czechs had to suffer due to shortages of food and consumer goods under communist rule. At that time, she and her husband had been largely protected from experiencing such economic difficulties, but that changed drastically for her and her son after her husband was arrested.

[wiki]Miroslav Lehký[/wiki], a scholar who has conducted research for the Prague-based Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes on communist repressions in Czechoslovakia, found documentary evidence about hundreds of thousands of Czechs and Slovaks who were victims of communism.

The fabricated political trials that the communist regime used to eliminate the opponents of the regime, which were based on investigations carried out by the State Security Service (“StB”) using torture and gross physical and psychological violence, resulted in the conviction of more than 257,000 people between 1948 and 1989, and if we include the people convicted by martial courts, the number exceeds 267,000 people. The very archival documents of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (“UV KSČ”) dating back to the 1950s list almost 27,000 people convicted for “anti-state crimes” between 1948 and 1952. The people were sentenced to severe imprisonment (15 or 25 years, or for life) and their personal property was forfeited and their civic and political rights taken away from them. A total of 248 people (including one woman) were executed for political reasons. 15

Miroslav Lehký also made observations similar to those made in her books by Heda Margolius Kovály by about the isolation of the people in Czechoslovakia forced on them by the communist regime, although in the case of certain communist officials and activists, the intellectual isolation was also self-imposed.

The totalitarian regime in Czechoslovakia could not exist without isolating its citizens from each other (using terror, violence, and an atmosphere of fear, distrust, and suspicion) and isolating its citizens from the free world around them. The communist ideology was based on a fictitious vision of the world, world order, and the human being. Thus, any confrontation of the ideology with reality posed a lethal threat to the regime. 16

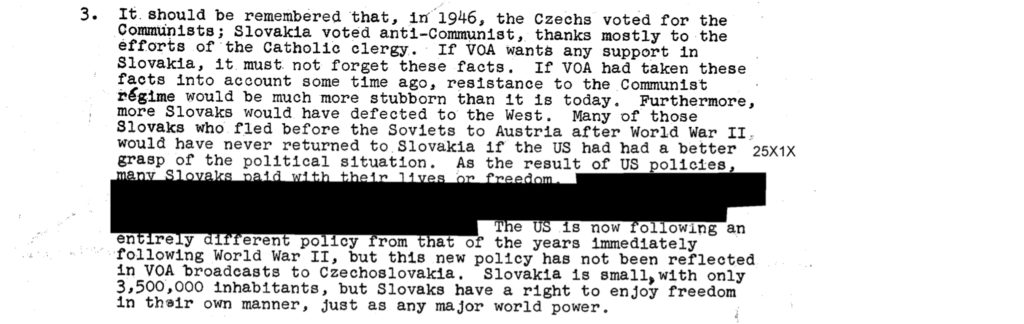

A Slovak View

There were not only differences in how various Western broadcasters were perceived by “hard line” and ordinary Communist Party members versus the rest of the population, but also differences between how Czechs and Slovaks in Stalinist Czechoslovakia saw these broadcasts, with Slovaks being more critical toward the Voice of America, according to a CIA report dated June 17, 1953. By that time, the Voice of America was already partially reformed and Radio Free Europe was transmitting massive amounts of uncensored information about the situation in Czechoslovakia since the station started broadcasting in 1950.

It appears, however, from the two CIA reports, that VOA programming was still substandard for some listeners. The CIA’s source was particularly critical of VOA broadcasting in Slovak.

In Slovakia, there is open criticism of VOA’s Czechoslovak programs because they offer no hope of Slovakia ever becoming an independent state. Slovaks do not recognize any so-called Czechoslovak nation; they consider themselves a different nationality. VOA broadcasts to Czechoslovakia, in nu opinion, dwell on an ideology with which the majority of Slovaks do not agree. Although the broadcasts are in both Czech and Slovak, the Slovak is so poor that the people make jokes about it.

17

…

Many of the programs are very unpopular in Slovakia and result in bitter criticism of VOA. The Slovaks are not interested in hearing praise of Czech Sokol activities, Czech cultural activities, Dr. Eduard Benes, or the other things which are completely Czech. VOA broadcasts to Czechoslovakia may be compared with Radio Prague broadcasts prior to 1939 and between 1945 to 1948. As far as Prague is concerned, Slovakia has always been a peripheral area, and the Slovaks are completely fed up with this attitude.

…

It should be remembered that, in 1946, the Czechs voted for the Communists; Slovakia voted anti-communist, thanks mostly to the efforts of the Catholic clergy. If VOA wants any support in Slovakia, it must not forget these facts. If VOA had taken these facts into account some time ago, resistance to the Communist regime would be much more stubborn than it is today. Furthermore, more Slovaks would have defected to the West. Many of those Slovaks who fled before the Soviets to Austria after World War II, would have never returned to Slovakia if the US had had a better grasp of the political situation. As the result of US policies, many Slovaks paid with their lives or freedom.

…

The US is now following an entirely different policy from that of the years immediately following World War II, but this new policy has not been reflected in VOA broadcasts to Czechoslovakia.

Communist Propaganda in Early Voice of America

In her book, Margolius Kovály does not specifically mention the Voice of America, making direct references instead to RFE and the BBC, but the source quoted in the 1953 CIA report alluded to a little known historical fact that during World War II VOA had been dominated by pro-Soviet officials and pro-communist broadcasters who promoted Soviet propaganda and Russia’s influence over Eastern Europe.

The head of VOA’s Czechoslovak Desk during World War II, Dr. Adolf Hoffmeister, left the United States after the war, joined the Czechoslovak Communist Party and worked as a diplomat. He eventually had a falling out with the Czechoslovak regime. A member of VOA’s Polish Desk during the war, Stefan Arski, became later for many years a key anti-U.S. propagandist for the communist regime in Warsaw. Arski never broke with the Polish party and received many state awards for his work as a communist journalist.

The source quoted in the CIA report asserted that some individuals who supported the communist takeover in Czechoslovakia in 1948 were still preparing VOA programs in the early 1950s.

It is the opinion of the Slovaks that members of the so-called Czechoslovak National Council in the US control most VOA broadcasts to Czechoslovakia. These are people who were responsible, either directly or indirectly, for the assumption of power by the Communists in 1948. The reasoning in Slovakia runs something like this: “Are these the people we are supposed to listen to? Are these the people who want to run the country again? With the support of the US, these people will again give the orders on how to run the country”. The members of the Czechoslovak National Council in the US represent a very small minority; they never cared about the welfare of the Slovak people, and now are interested only in enriching themselves. Eighty-five percent of the Slovak population is Roman Catholic. About 700,000 Slovaks, mostly Roman Catholics, are living in the United States, and those people in Slovakia want to know why they never hear on VOA about these people, their organizations, such as the Catholic Union, Slovak League, Brotherhood of Slovak Catholics, and their various publications in the, US. I would suggest that this group of Slovaks develop a separate program of broadcasts to Slovakia. 18

In the initial years of the Cold War, the Voice of America was not of much help in countering Soviet propaganda, having been earlier a conduit for Soviet propaganda during World War II. This VOA’s initial failure was exposed by many critics, including the new acting chief of VOA’s Romanian Service, Dr. John Cocutz, who had testified in Congress in 1953 that many VOA managers and broadcasters “didn’t know what it was all about, what communism was.” 19

In his congressional testimony, Dr. Cocutz quoted his supervisor telling him that he [Cocutz] was under the mistaken impression that the Voice of America existed to fight communism, “while we are not,” the VOA official in charge of broadcasts to the region reportedly said. 20 As he testified later in Congress, Dr. Cocutz told his boss that he was surprised to learn that VOA was not in the business of fighting communism.

Well, I am surprised, because I left my job at the University of Georgia purposely to fight against communism. There is no business for me to be here then. I can go back to the university, if I can’t fight communism here. 21

Naivety about communism was not limited to idealistic party members behind the Iron Curtain. Soviet propaganda managed to confuse a lot of people in the West, including a number of left-leaning intellectuals and journalists. One of the many was Pulitzer Prize New York Times reporter [wiki]Walter Duranty[/wiki] who had lied in his reports about the show trials in Moscow and the regime-created famine in Ukraine in the 1930s.

Some of those deceived by Soviet propaganda included from 1942 to 1945 early Voice of America officials and broadcasters and later some U.S. State Department diplomats who from 1945 to 1953 were responsible for directing VOA programs. According to Dr. Cocutz’s testimony, the VOA official in charge of radio programs to Eastern Europe explained to him in the early 1950s the need to refrain from criticizing communism using arguments very similar to how idealistic communists justified their work for the Czechoslovak regime and their initial refusal to believe what Radio Free Europe was saying about communism.

Then he added another remark, saying that he was informed by some people that communism helped some poor people in some parts of the world… 22

Fortunately, other prominent Americans, aware of the power of Soviet propaganda, pushed hard to create Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty and advocated for reforming the Voice of America. Personnel and programming reforms at VOA took several years and their progress varied from service to service.

Czechs and Slovaks interviewed by the CIA in the early 1950s offered various advice for the Voice of America. Some of the advice was more appropriate for Radio Free Europe which already successfully produced such programs.

…a weekly program be directed at Communist Party members, during which the Party would be attacked relentlessly. Purges of long standing Party members their offenses and threatened punishments should not only be reported but also made the subject or commentaries. The life and deeds, promises and lies of communist leaders should be publicized. By the same token, rank and file CP members should be warned, but it should be pointed out that they will be judged by their deeds and not just by Party membership. Such a program would cause chaos and disorganization in Czechoslovakia, and increase passive resistance on the part or the Czechs. 23

The Czech source quoted in the CIA report emphasized the need for bold but also responsible journalism.

In conclusion, the Voice of America is a part of the daily life or the millions in Czechoslovakia; indeed the whole nation tries to tune in VOA every day. The greater the number of people listening to VOA, the greater the responsibility of those making these broadcasts. A great deal of harm can be done by irresponsible broadcasting.

In this connection

(a) A greater sense or responsibility should be adopted and more care should be devoted to factual reporting.

(b) More emphasis should be placed on the survival of people behind the Iron Curtain and less to the American way or life; ie, more attention should be devoted to events and problems in Czechoslovakia.

(c) More of the human touch and more optimism should be included in programs.

(d) The Communist Party should be more severely attacked; government leaders should be assailed, but not to such an extent that the plain people would be forced to stick with the CP out of desperation.

(e) The people of the CSR should be convinced of the growing strength of the West; VOA should keep harping on the backwardness of the Soviet orbit in all fields of science.

(f) All programs should be prepared with the thought that the Voice of America is playing a major role in shaping the future course or history during this crucial struggle. 24

The Slovak source in the CIA report offered additional advice for VOA from a perspective of a Slovak listener to Western broadcasts.

I would like to make the following suggestions with regard to VOA broadcasts:

a. Broadcasts should support the most effective battle against Communism.

b. Further, they ‘should emphasize cooperation among the European nations.

c. They should not try to force the idea of national union upon a people such as the Slovaks.

d. A more responsible group should be put in charge of the programs. 25

Early Non-Communist Opponents and Escapees from Czechoslovakia

By the early 1950s, many people in Czechoslovakia who suffered daily shortages of food and other basic consumer goods were eager to get uncensored news from Western sources. By that time, VOA was already beginning to include more information on communist repressions behind the Iron Curtain. Its initial pro-communist bias slowly diminished and was eventually eliminated as a result of strong criticism from the U.S. Congress, which prompted internal personnel changes and other reforms. Most of the information on human rights abuses, however, continued to come from Radio Free Europe which specialized in providing local news and hard-hitting commentary.

Among faithful listeners to Western broadcasts were thousands of Czechs and Slovaks who tried to make daring escapes to the West thorough the well-guarded Iron Curtain. Some succeeded, but many more were shot by communist border guards or arrested, tried and sentenced to prison terms. The stories of those who succeeded to escape were presented in RFE and VOA programs. One archival United Press Photo dated March 22, 1954, showed four members of a Czech escapee family of ten being interviewed by the Voice of America. They can be seen smiling but with their eyes masked “to prevent identification by their Red enemies,” as the photo’s caption said. The photo also included this description:

[They] make no attempt to cover their glad smiles, as they tell their compatriots behind the Iron Curtain via Voice of America just how good it feels to be free.

Early Opponents of Communism: Milada Horáková

While communist officials initially may have not seen the need to listen to such Western broadcasts or were too afraid to listen or afraid to admit to anyone that they listened, regular listeners included opposition figures and millions of Czechs and Slovaks. One of the few brave individuals who showed courage and dignity in opposition to communism was [wiki]Milada Horáková[/wiki], a human rights lawyer who was tried and executed by the regime in 1950, two years before Rudolf Margolius’ trial and execution. [See: [wiki]Milada (film)[/wiki] and read and listen to Radio Praha program, “Milada Horáková: Dignity in the Face of Fanaticism.”] A survey conducted by Radio Free Europe among visitors from Czechoslovakia in the West in 1963 showed that weekly listenership to Radio Free Europe at about 30% of adult population, VOA at about 15% and BBC slightly less than 10%. Surveys were conducted among travelers from Eastern Europe by independent research firms in Western Europe. 26

While communist officials initially may have not seen the need to listen to such Western broadcasts or were too afraid to listen or afraid to admit to anyone that they listened, regular listeners included opposition figures and millions of Czechs and Slovaks. One of the few brave individuals who showed courage and dignity in opposition to communism was [wiki]Milada Horáková[/wiki], a human rights lawyer who was tried and executed by the regime in 1950, two years before Rudolf Margolius’ trial and execution. [See: [wiki]Milada (film)[/wiki] and read and listen to Radio Praha program, “Milada Horáková: Dignity in the Face of Fanaticism.”] A survey conducted by Radio Free Europe among visitors from Czechoslovakia in the West in 1963 showed that weekly listenership to Radio Free Europe at about 30% of adult population, VOA at about 15% and BBC slightly less than 10%. Surveys were conducted among travelers from Eastern Europe by independent research firms in Western Europe. 26

The New York-based Committee for a Free Europe, the organization composed of prominent private Americans working with U.S. government officials who created Radio Free Europe and placed it initially under the secret watch of the Central Intelligence Agency, produced in 1951 a comic book commemorating Milada Horáková‘s life. [Read and listen to Radio Praha program “National Archive Analysing New Milada Horakova Documents.”]

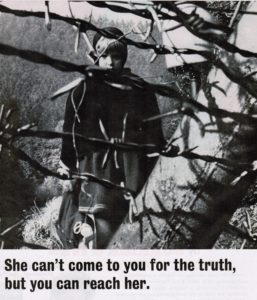

An ad placed in American magazines by the Radio Free Europe Fund in 1966 described a young listener to RFE broadcasts in Czechoslovakia.

The truth can become a very

precious thing to a young mind

in a closed country:“Dear Friends,

I began listening to your broadcasts when I was a small child.

Today I am 22.

And for most of what I know about the world, I have to thank Radio Free Europe.”

The young woman who wrote that letter lived in Communist-ruled Czechoslovakia.

Ten years ago, she though the world ended with that ugly barbed wire fence.

Today she knows different. And what’s more important, she knows who built it.

There are 82 million people like her living in the Iron Curtain countries of Czechoslovakia, Rumania, Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary. And more of them listen to Radio Free Europe than ever before.

The news, not only of their own country, but of the outside world, is broadcast without bias or distortion and in their own language.

Radio Free Europe is on the air up to 19 hours every day.

The one-time Communist monopoly of information in Eastern Europe has been broken.

The truth is getting through, helping millions work toward their freedom.

And with that as a goal, a great many people have a great many more reasons to go on living.

Give to Radio Free Europe, Box 1966, Mt. Vernon, N.Y.

Some Communists Returned to Power After Imprisonment

Some high-ranking members of the Communist Party, even those who had been imprisoned during the Stalinist period and survived, including Czechoslovak President [wiki]Ludvík Svoboda[/wiki], returned to high-level party and government posts upon their release from prison following the death of Stalin in 1953 and the limited liberalization in the Soviet Union initiated by Nikita Khrushchev. Svoboda opposed the Soviet invasion but later cooperated with the Soviets and supported crackdowns on the remains of free press and anti-communist dissidents. Soviet Russia was the ultimate arbiter of keeping East European communist leaders in power and they usually justified and excused their cooperation with Moscow by claims that any effective opposition would lead to a bloody Soviet invasion. One of such imprisoned communist leaders in Poland was [wiki]Władysław Gomułka[/wiki] who after his return to power in 1956 and a brief period of relative liberalization also presided over a crackdown on dissidents. Gomułka survived Stalin because, despite pressures from Moscow, the Polish Communist Party procrastinated and did not stage a show trial for its imprisoned leaders. Thousands of Polish non-communists, however, were tried and executed. Even though his wife, [wiki]Zofia Gomułkowa[/wiki], was Jewish, several years after his return to power Gomułka helped to initiate an anti-Semitic campaign to purge Polish Jews from party, army and government positions in Poland in 1968 in a campaign similar to the anti-Semitic purges conducted earlier in the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. Polish Jews were not arrested in 1968, but they lost their jobs and were forced to leave Poland. Gomułka and his wife supported the anti-Semitic campaign. The pattern of anti-Semitism among Soviet and East European communist parties put a lie to Soviet communist claims of the movement’s opposition to fascism and other racist ideologies.

Gomułka also strongly supported the 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia to squash reforms of the 1968 [wiki]Prague Spring[/wiki] initiated by the Czechoslovak Communist Party under pressure from the population. Ultimately, it was almost all about power and privilege to which communist elites held on for as long as the Soviet Union was willing to support them with the threat of a military invasion in case a popular anti-communist uprising would be allowed to get out of control.

Aftermath

Rudolf Slánský, Rudolf Margolius and the others convicted in the 1952 Slánský show trial were quietly rehabilitated by the Supreme Court in communist-ruled Czechoslovakia in 1963. The rehabilitation came much later than for some communists in the Soviet Union and in Poland and was done without much publicity. Communist Czechoslovak President Ludvík Svoboda awarded the Order of the Republic posthumously to Rudolf Margolius.

An early opponent of communism in Czechoslovakia, dissident writer [wiki]Pavel Tigrid[/wiki] saw Margolius as both a communist idealist and a victim of communism.

Margolius… survived the Nazi concentration camps and after the war enrolled into the Communist Party from the real conviction: that never again would be repeated what had happened in the past, that no one would be persecuted for his or hers racial, national or social origins, in order for all people to be equal, in order to establish an era of real freedom. A couple of years later the comrades succeeded in what the Nazis had not managed: they killed him. 27

After her escape form Czechoslovakia 1968 as the country was being invaded by the Soviet Union with the help of some of the other Warsaw Pact armies, Heda Margolius Kovály lived in the United States and worked at the Harvard Law School Library. For several years in the 1970s, he worked as a freelance reporter for the Voice of America Czechoslovak Service under a pseudonym Kaca Kralova. It was a common practice for at least some VOA broadcasters and freelancers to use pseudonyms during the Cold War in order to protect family members and friends still in countries behind the Iron Curtain from possible reprisals. She worked mainly with Vojtech Nevlud in the Czechoslovak Service, sending scripts to him for approval and then reading them over the phone to be recorded in a VOA studio in Washington. Her reports, mostly on cultural topics, would have been used by the Czechoslovak Service in the second half of each broadcast, mostly about 17 minutes into the early half hour shows and about 25 minutes into the one hour shows. During the 1970s, Voice of America foreign language services were again largely restricted in their ability to originate their own political reports and commentaries. Most of the service-originated reporting was on American topics dealing with culture and non-political issues, such as the reports written by Margolius Kovály, although some original political reporting, carefully monitored by the management, was allowed from in the 1970s time to time in VOA’s East and Central European language services. It was a period of détente in Washington’s relations with the Soviet Union. Both political and budgetary restrictions were placed on VOA by the Nixon and Ford administrations. Heda Margolius Kovály produced for VOA several dozen scripts in Czech between 1973 and 1976. She most likely used the pseudonym to appear as an ordinary member of public rather than as an intellectual speaking to others from an “elevated” platform, and also mainly to protect any friends of hers still in Czechoslovakia.

Page from a report for Voice of America Czechoslovak Service by Kaca Kralova, radio name of Heda Margolius Kovaly. Photo: Courtesy of Margolius Family Archive.

Heda Margolius Kovály returned to Prague with her second husband in 1996 and died in 2010. [wiki]Ivan Margolius[/wiki], her son from her marriage to Rudolf Margolius, left Czechoslovakia in 1966, knowing that political repression would prevent him from going to a university and getting more than a menial job. He settled in the United Kingdom where he became a successful architect, author, and propagator of Czech culture and technology.

Jana Horakova Kansky, the daughter of Milada Horáková, was for many years not allowed to leave Czechoslovakia to join her father who had escaped to the West. She was also not allowed to study at a university. She did not emigrate to the United States until 1968. [Read and listen to Radio Praha program, “Jana Horakova-Kansky – Still Proud of Mother’s ‘Enormous Courage’.”]

While most of the surviving major Nazi mass murderers were tried and punished after the war, most of the communist officials, torturers who extracted false confessions, and judges who sent Milada Horáková, Rudolf Margolius and other innocent people to their deaths, avoided punishment or received only minimal sentences after the end of the Cold War.

Later in the Cold War, the reformed Voice of America Czechoslovak Service played a major role in bringing uncensored news to Czechoslovakia. It included journalists Vojtech Nevlud and Frantisek Lysy.

Pavel Pecháček, a Czech journalist who was director of VOA’s Czechoslovak Service and later served as director of RFE/RL’s Czechoslovak Service called the creation of RFE/RL and VOA “one of the greatest gifts the United States has bestowed on oppressed people living under totalitarian regimes.”

Zdenek F. Sedivy, who also served for many years as one of VOA’s employee union stewards, and Miro Dobrovodsky, profiled in a 2004 VOA English report, were some of the best known radio personalities in Slovakia.

“There were signatories for freedom. At that time, that was the kind of journalism… Under normal circumstances, it is not news if you are reading 25 names. But behind the Iron Curtain, if you read twenty-five names of people who had signed something against the regime, it was hot stuff, and a major story.”

To illustrate the importance of VOA’s news to the Slovak and Czech audiences, Mr. Dobrovodsky quotes a friend who returned from a visit to Bratislava, the capital of Slovakia, when it was still under the communist regime. His friend recalled that as he walked through the city night, a familiar tune – VOA’s old “Yankee Doodle” station I.D. – caught his ear:

“He said that he was walking in a new quarter of town, high-rises, you know, and at 9 PM he heard Yankee Doodle in stereo. And I said to him that we aren’t broadcasting in stereo. And he says, ‘No, no, no, but it’s August, every window is open, and when you hear it from a thousand windows, even quietly, it sounds like Yankee Doodle in stereo.’” 28

Ivan Medek “became a vital link to the outside world” after he started to report in the late 1970s as the VOA Czechoslovak Service correspondent in Vienna. [Read and listen to Radio Praha report, “Legendary Czech Broadcaster Ivan Medek Remembered.”]

Some of the on-the-ground reporting in the period shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall and during the Velvet Revolution came from VOA’s English roving East European correspondent Jolyon Naegele. [Read and listen to Radio Praha program, “Jolyon Naegele – A Voice of the West for Many Czechs in the 1980s.”]

We will never know what exact impact Western radio broadcasts had on members and leaders of the Communist Party and government officials in Czechoslovakia in the early years of communist rule, but the contribution of both RFE and VOA to the peaceful fall of communism is unquestionable. In the end, communism fell in Czechoslovakia and in other countries not because of anything communist leaders did to reform the system but because the centralized socialist economy failed, the Soviet Union started to disintegrate and the population lost its fear of the authoritarian regimes.

Ivan Medek and other journalists established close contacts with the Czechoslovak dissident movement Charter 77 and reported on it for VOA. Radio Prague reported, “As former president Václav Havel told Czech Television, that role was crucial.”

Without his work at Voice of America, the Charter and the whole movement would, by a long way, not have had the same weight, influence and reach. 29

Photo of former anti-communist dissident [wiki]Václav Havel[/wiki] visiting Voice of America in February 1990 as the last President of Czechoslovakia. The photo is from the archive of Marek Walicki, former RFE Polish Service broadcaster and former deputy director of Voice of America Polish Service. Havel served as the first President of the Czech Republic from 1993 to 2003. He often praised RFE and VOA broadcasts and invited RFE/RL to move from Munich, Germany to Prague. The move was completed in 1995.

Heda Margolius Kovály died in Prague in 2010. A book published in 2018 in English by her son, Hitler, Stalin and I: An Oral History, based on interviews with Heda Margolius Kovály by award-winning Czech film documentarian Helena Třeštíková, includes Margolius Kovály‘s assessment of the impact of Nazism and Communism on the 20th Century, the two totalitarian ideologies she managed to survive and outlive.

People ask me frequently what was worse, Nazism or Communism. It is difficult to decide. Nazism was clearly a gangster ideology that encouraged people to the worst behavior, plotting toward wars, calling one race superior to others and simply killing people and stealing; whereas, the Communists abused people’s altruism and kindness. They allured them with talk of humanity’s highest ideals, so it is difficult to say which was worse. I think Communism was worse because it lasted longer, so they could actually do more evil and harm than the Nazis. The statistics say that Stalin murdered more people than the ones who perished in both of the world wars. 30

Unfortunately, the newest book has no references to Western radio broadcasts during the Cold War, but Margolius Kovály confirms once again that in the early, post-World War II years of communist-rule in Czechoslovakia, party members like herself and her husband initially rejected reports of the regime’s atrocities as fabrications and imperialist propaganda.

People were being arrested from the very beginning of the Communist regime, and when we found out we used to say: “Good God, how is it possible –such good people, and they’re traitors. They’re saboteurs. They wouldn’t have been arrested if they were innocent.” And we weren’t concerned any further. Or we got terribly angry: “How was it possible?” 31

Heda Margolius and her first husband Rudolf Margolius were not unique in being blinded by communist ideology and by its propagandists. Many people, both in Czechoslovakia and the in the West, were deceived by both Nazi and Soviet propaganda, including many people who called themselves “journalists.” Hitler had his European supporters outside of Germany. He had supporters in the United States before World War II.

The Communist Party USA consistently toed the Moscow line during the Hitler-Stalin Pact and while Stalin was planning to take over Eastern Europe with the help from naive President Franklin D. Roosevelt. American communists were doing everything possible to help Stalin succeed.

During the war, even the U.S. government-run Voice of America, a broadcasting unit within the Overseas Branch of the Office of War Information (OWI), became a pro-Soviet propaganda platform thanks to Stalin sympathizers among its key officials and actual communists among some its broadcasters.

Many other Western journalists in Europe and in the United States at first refused to believe in reports of Soviet atrocities and later tried to avoid reporting on them and their own failure to spot them.

During the war, VOA tried to cover up Stalin’s crimes and was reluctant to expose them even for a few years after 1945. In the 1970s, VOA censored Alexandr Solzhenitsyn for a few years in response to pressure from Moscow and Soviet propaganda.

Only Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty managed to avoid being tainted with repeating Soviet propaganda and resorting to censorship to make communism and the Soviet empire look better than they were. RFE and RL were one of the few Western institutions that were not corrupted by Soviet influence and disinformation.

Propaganda from Russia ruled by President Vladimir Putin continues to confuse a lot of people today. In this context, the initial political blindness of idealistic Czechoslovak communists who had experienced Nazism and the Holocaust is perhaps more understandable than the blindness of Roosevelt administration officials and quite a few pro-Soviet Western journalists. Propaganda is a powerful and dangerous weapon because it is often used to promote hatred, often with the help of journalists blinded by left-wing or right-wing ideologies and partisan bias.

Intellectual enablers of Fascism were roundly and justly condemned and the most brutal Nazi criminals were punished. Most Communists who had committed criminal acts avoided punishment and their intellectual enablers continue to be praised. In 2017, the Voice of America broadcast a program in which American Communist Angela Davis was hailed as a fighter for workers and women’s rights and not a word was said about her earlier support for the Soviet Union and her refusal to defend political prisoners in communist-ruled Czechoslovakia and independent trade trade union leaders jailed in communist-ruled Poland.

Genocidal crimes committed by Communists are still not widely known. Miroslav Lehký and others have called for an international debate to classify them as crimes against humanity.

A thorough settlement of such crimes and a clear declaration thereof is not only required in terms of justice – it is also of utter importance for our present and future.

The history is not over and we can see attempts at establishing other totalitarian regimes that may be much more refined and sophisticated than the previous ones. They test us – the extent to which we will make concessions.

Our unwillingness or inability to deal with our past thoroughly may endanger our freedom and democracy and serve such regimes in the future. 32

There is also the need to avoid demonizing groups and political opponents as both Nazis and Communists did. Margolius Kovály’s advice was: people should try to be tolerant toward each other and avoid being consumed by hate. It is an especially good advice for intellectuals and journalists.

I wish for the world to come to its senses, for people to finally agree and stop hating each other. The whole of my life, I have tried not to hate, to overcome those terrible events that happened to me without hating anyone. When people stop hating their fellowmen just because they are a bit different, or richer, or poorer, or less intelligent, when they have a bit of understanding for each other and wish each other all the best, then the world will be a sensible place. However, if people want to settle their debts and find pleasure in vindictiveness and the suffering of their fellowmen, then all is lost; that will be the end. Now we have the available machinery; we could explode it all. 33

Colorized Photo of Milada Horáková at her trial by Cassius Chaerea is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Ted Lipien is a former director of VOA Polish Service and former VOA acting associate director.

SUPPORT THE WORK OF COLD WAR RADIO MUSEUM

IF YOU APPRECIATE SEEING THESE ARTICLES AND COLD WAR RADIO MEMORABILIA

ANY CONTRIBUTION HELPS US IN BUYING, PRESERVING AND DISPLAYING THESE HISTORICAL EXHIBIT ITEMS

CONTRIBUTE AS LITTLE AS $1, $5, $10, OR ANY AMOUNT

CLICK TO DONATE NOW

Notes:

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Slovak Reaction to VOA Broadcasts,” June 17, 1953. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80-00810A001400310007-5.pdf. ↩

- Voice of America, “VOA History.” Last accessed January 3, 2019, https://www.insidevoa.com/p/5829.html. ↩

- Margolius Kovály, Heda. Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1989. ↩

- Heda Margolius Kovály, Under A Cruel Star: A Life in Prague 1941-1968 (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1989), p. 11. ↩

- Margolius Kovály, Under A Cruel Star, p. 11. ↩

- Margolius Kovály, Under A Cruel Star, p. 11. ↩

- Margolius Kovály, Under A Cruel Star, p. 40. ↩

- Margolius Kovály, Under A Cruel Star, p. 94. ↩

- Margolius Kovály, Under A Cruel Star, p. 94. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Voice of America Broadcasts to Czechoslovakia,” May 20, 1952. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0002653697. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Voice of America Broadcasts to Czechoslovakia,” May 20, 1952. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0002653697. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Voice of America Broadcasts to Czechoslovakia,” May 20, 1952. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0002653697. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Voice of America Broadcasts to Czechoslovakia,” May 20, 1952. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0002653697. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Voice of America Broadcasts to Czechoslovakia,” May 20, 1952. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0002653697. ↩

- Miroslav Lehký, “Classification of crimes committed between 1948 and 1989 and the prosecution of these crimes after 1990.” Last accessed January 3, 2019, http://old.ustrcr.cz/data/pdf/publikace/sborniky/crime/lehky-miroslav.pdf ↩

- Miroslav Lehký, “Classification of crimes committed between 1948 and 1989 and the prosecution of these crimes after 1990.” Last accessed January 3, 2019, http://old.ustrcr.cz/data/pdf/publikace/sborniky/crime/lehky-miroslav.pdf ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Slovak Reaction to VOA Broadcasts,” June 17, 1953. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80-00810A001400310007-5.pdf. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Slovak Reaction to VOA Broadcasts,” June 17, 1953. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80-00810A001400310007-5.pdf. ↩

- Voice of America: Report on the Government Operations Made by Its Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1954), p. 3. ↩

- Voice of America: Report on the Government Operations Made by Its Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1954), p. 4. ↩

- Voice of America: Report on the Government Operations Made by Its Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1954), p. 3. ↩

- Voice of America: Report on the Government Operations Made by Its Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1954), p. 3. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Voice of America Broadcasts to Czechoslovakia,” May 20, 1952. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0002653697. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Voice of America Broadcasts to Czechoslovakia,” May 20, 1952. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/document/0002653697. ↩

- Central Intelligence Agency, “Slovak Reaction to VOA Broadcasts,” June 17, 1953. Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/CIA-RDP80-00810A001400310007-5.pdf ↩

- R. Eugene Parta, “Listening to Western Radio Stations in Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Romania and Bulgaria: 1962-1988.” “Longitudinal Listening Trend Charts.” Prepared for the Conference on Cold War Broadcasting Impact, Stanford, California, October 13-15, 2004. ↩

- Pavel Tigrid, Kapesní průvodce inteligentní ženy po vlastním osudu (Toronto: 68 Publishers, 1988), p. 97. ↩

- Voice of America, “A VOA Journalist Looks Back – 2004-04-09.” Last accessed January 2, 2019, https://www.voanews.com/a/a-13-a-2004-04-09-32-1-66344307/545153.html. ↩

- See Radio Praha report, “Legendary Czech Broadcaster Ivan Medek Remembered.” ↩

- Heda Margolius Kovály (Author), Helena Tretíková (Editor), Ivan Margolius (Translator), Hitler, Stalin and I: An Oral History (Los Angeles: Doppel House Press, 2018), p. 153. ↩

- Margolius Kovály (Author), Tretíková (Editor), Ivan Margolius (Translator), Hitler, Stalin and I: An Oral History, p. 153. ↩

- Miroslav Lehký, “Classification of crimes committed between 1948 and 1989 and the prosecution of these crimes after 1990.” Last accessed January 3, 2019, http://old.ustrcr.cz/data/pdf/publikace/sborniky/crime/lehky-miroslav.pdf ↩

- Margolius Kovály (Author), Helena Tretíková (Editor), Ivan Margolius (Translator), Hitler, Stalin and I: An Oral History (Los Angeles: Doppel House Press, 2018), p. 152 ↩